What matters most in sustainable business?

“Things which matter most must never be at the mercy of things which matter least.”

Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe

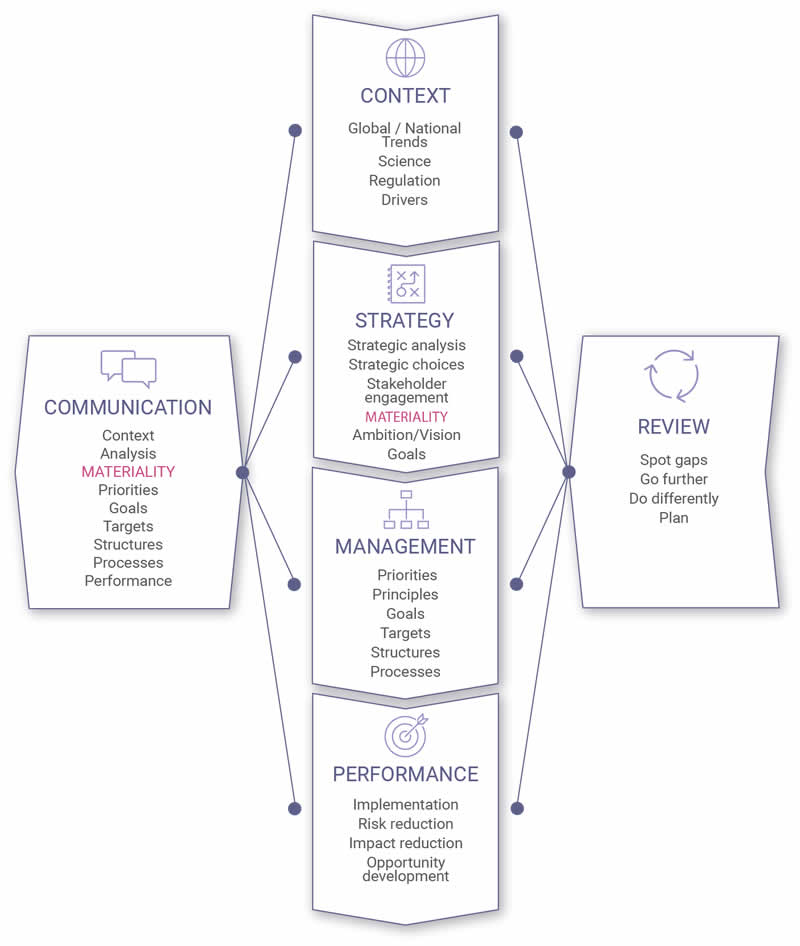

Materiality is the difference between a weak sustainability strategy or approach and one that’s logical, planned and based upon what’s important.

A term drawn from accounting and the legal profession, materiality simply means what’s relevant and important.

Materiality assessment is pivotal to a serious approach to sustainable business or ESG because it demonstrates that you have analysed, understood and prioritised the social and environmental issues that present sources of risk and opportunity for you and your stakeholders.

At a glance…what types of issues are likely to be material for you?

- Where your organisation’s activities pose a risk to the environment or society.

- Where environmental and/or social issues present a risk to your organisation.

- Where an issue affects your organisation’s core operations.

- Where an issue does or could affect your reputation.

What is Materiality?

Materiality is a process used to identify priority issues for management. It’s a recognised accounting term – a test used to assess what should be included in financial statements. More recently, the concept has been widened to provide a way of assessing and prioritising the importance of non-financial issues (environmental and social) in the context of overall business priorities, management and performance.

Another critical distinction when used for sustainability, CSR or ESG is that third party views are included in the concept of relevance, providing the means to integrate stakeholder perspectives on organisational priorities and impacts.

Materiality assessment and target setting, performance management and disclosure of identified material issues provide the ‘narrative’ core to sustainability management and is central to sustainability reporting.

The bottom line….

If you think you are serious about sustainability but have not conducted some form of materiality assessment, then perhaps you are not as serious as you thought.

Strategy Services

Effective sustainability strategy helps leaders from businesses and NGOs navigate the complexities of sustainability and identify opportunities.

Assessing materiality

There is currently no single standardised approach to materiality assessment (but see below about CSRD and Double Materiality). Several methods can be used to identify whether issues are considered material. In practice, organisations can use approaches flexibly if they are transparent about their methods and results.

A useful way of testing whether an issue is material was developed by Accountability in the publication ‘Redefining Materiality’. They proposed a five-part test:

Test 1: Direct, Short-Term Financial Impacts: including any sustainability issues which have the potential to influence short-term profitability, the direct cost and availability of capital, or are likely to become subject to future regulation or taxation.

Test 2: Policy-Related Performance: this test can be used to gauge the potential mismatch between a company’s stated policy aims and objectives in business sustainability and actual performance in practice. This test is felt to be particularly attractive from a risk perspective, enabling assessment to be made of the potential for adverse publicity, litigation or claims.

Test 3: Business Peer-Based Norms: this test offers an important means of extending definitions of what is material, based on the activities of leading companies, competitors and peers. Analyses against accepted sectoral priorities and concerns will also offer a useful insight.

Test 4: Stakeholder Behaviour and Concerns: the fourth materiality test is concerned with the identification of internal company practices, which could have significant impacts on external decisions and behaviours. The main difficulty is deciding which opinions are likely to translate into behaviour and which are not.

Test 5: Societal Norms: in many respects, this test offers a more rounded indication of future market conditions and attitudes. In some cases, the scope and emphasis of prospective legislation will dictate these norms. Strong indications can also be identified from the practices of leading institutional investors, or from voluntary codes of practice, such as the UN Global Compact, the SASB Standards or the TCFD. Increasingly, they will also be influenced by public views on which company practices serve the wider interests of society. The responses of many companies towards the perceived risks associated with genetically modified foods offers a good example of how public attitudes have influenced market offerings.

Any of the above tests might identify an issue which is likely to be, but will not certainly be, material. If an issue is identified by more than one test it is more likely to be material.

Sector based materiality – useful resources

Some initiatives have worked to identify, on a sectoral basis, which issues are likely to be material.

The SASB (Sustainability Accounting Standards Board) has developed a Materiality Map, identifying, at a high level, issues which are material for 11 business sectors.

Another useful resource is the Sustainability Yearbook, which presents, on a sector by sector basis, the high-level issues which should be considered as priorities for management.

However, it is important to highlight that whilst each of the above resources will give you an indication of the sort of issues which you should be considering as material, they will not tell you exactly how they manifest for your organisation, the risk that your current management of the issues presents or the specific views of stakeholders on your impacts.

What are the issues which should be considered?

Material sustainability issues comprise the environmental and social impacts of your organisation, and those which affect you organisation, including its value chain as a whole, in addition to those issues which are identified by stakeholders of your organisation (either through direct engagement or by proxy). For a brief insight into stakeholder engagement, see our article: Stakeholder engagement – building resilience.

Material issues may also be those which are not impacts per se, but where environmental and social issues in the wider world present actual or potential sources of risk and opportunity which should also become management priorities (see also the section below ‘Material when? – the case for future proofing’).

Collectively, all these issues represent a pool of potentially material topics. These are then prioritised in order to identify a shorter list of issues which become prioritised for management.

Translating assessment into management priority

Once you have identified what your material issues might be, they need to be analysed in order to identify priorities for management. That is, which of them should be the focus of sustainability ambition, targets and performance improvement.

Two commonly used approaches are described here.

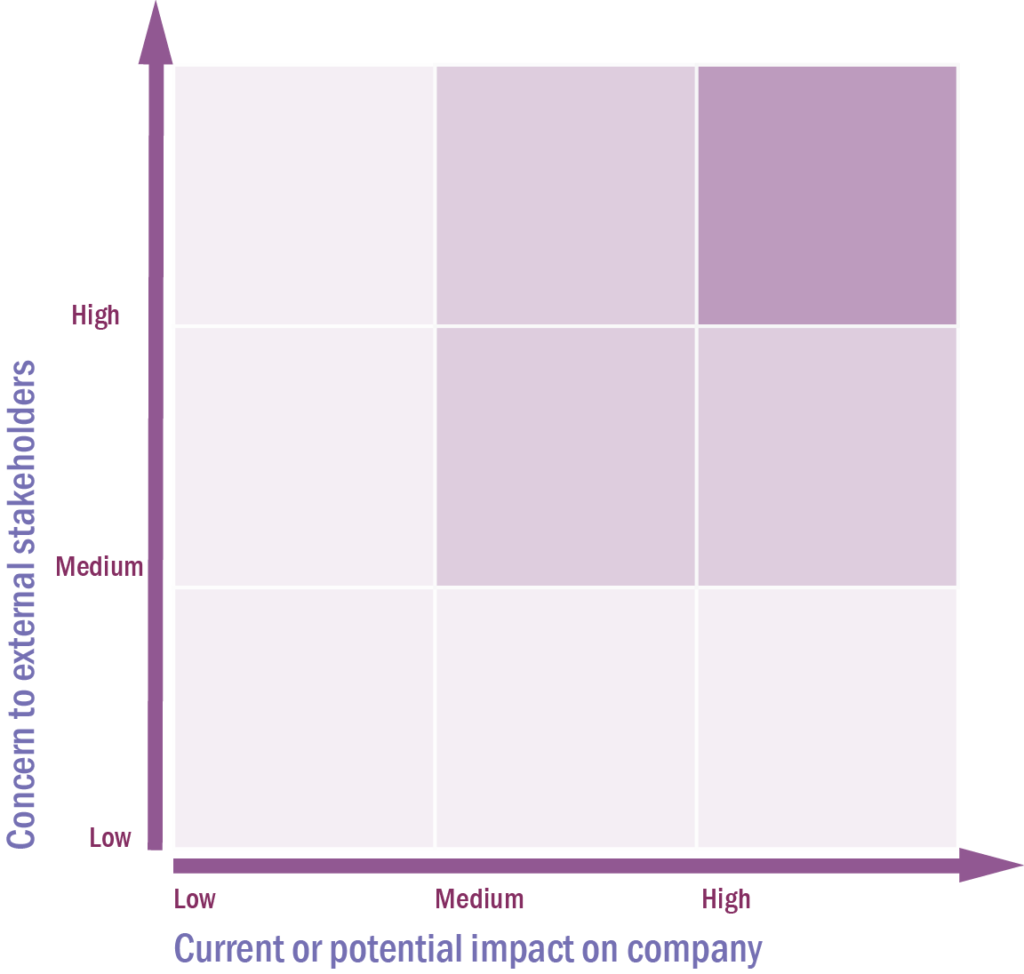

1. Materiality matrix

A materiality matrix can be used to prioritise sustainability issues identified by the company and by engagements with stakeholders.

Each identified issue should be rated as low medium or high from two perspectives, that of a stakeholder and that of the company.

Those issues in the shaded sectors above are material issues for management. Those in the dark, (high-high rated) sector above are priority material issues.

2. Questions for testing materiality

An, alternative, more integrated approach to materiality assessment is to consider the following questions in relation to each identified sustainability issue:

- Focus (Vision): to what extent does a focus on this issue support the dimensions of our sustainability vision?

- Focus (Materiality): how relevant is a focus on this issue to our business in terms of reputation, performance improvement etc?

- Risk: what is the risk that this issue could pose to our business model and resource dependencies and what is the potential contribution of action on this issue to the minimisation of financial, social and environmental risks?

- Value: would activity focussed on this issue support us in:

- Developing a resilient and sustainable business model?

- Protecting market share?

- Building market share?

- Strengthening supplier relationships?

- Responding to customer and stakeholder concerns?

- Ensuring security of supply?

- Creating new business?

- Building/enhancing/reputation?

- Delivering our sustainability leadership ambitions?

- Spheres of control/Influence and concern: for this issue, do we have control / influence or concern?

- Importance: what priority should this occurrence have to management focus and resources (High/Medium/Low)?

In practice, the two approaches can also be used together.

The bottom line….

Whichever approach you use, it’s crucial that you start with an inclusive and wide-ranging set of issues – but it’s especially important for the question-based approach if you’re not involving external stakeholders. You can scope the range of possible views by studying sectoral guidance and looking at the views of different NGOs and pressure groups. You can (and should) also include different stakeholders from across your organisation in your process.

Material to whom?

A key challenge in materiality assessment is that an issue may be material from one perspective, and not from another. For instance, an NGO might consider that water pollution from a company’s manufacturing site is material, as it could have a significant effect on the health and wellbeing of the community and its environment. However, for the company, that site might not be significant when put in the context of all their sites.

This is why materiality is not simply a test of financial significance, it is a balanced assessment on internal and external perspectives across a range of conceptions of risk and value.

CSRD Double Materiality – Risk to and risk from

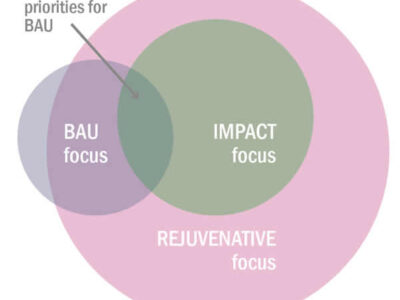

Most companies undertaking a materiality assessment will use the ‘lens’ of their own organisation when it comes to making a final decision on what is material. This is considered a “risk-to” lens – e.g., how might this external issue affect our ability to operate or perform?

They will be asking: ‘is this material to us and why?’ As mentioned above, an aspect of this is understanding the perspectives of stakeholders and rating these in the context of business priorities.

However, unless there are specific circumstances requiring an ‘exceptional’ focus upon social licence to operate, or compliance with specific social value regulations, rules or committed norms it would essentially be ‘the business’ making a final decision on what is material (albeit with a requirement to be able to disclose and defend decision making).

This is the approach taken by the IFRS in their Sustainability Standards, which consider that environmental and social issues are material if they do or could affect enterprise value, and therefore “information is material if omitting, obscuring or misstating it could be reasonably expected to influence investor decisions.”

However, the enterprise value (or company) lens is generally considered to be inadequate to reflect the fundamental point of sustainability management – to understand, manage and minimise the impact of an organisation’s operations on the planet and society – the “risk from” the company.

This combination of “risk to” and “risk from” approaches is referred to by a number of names but within the European Union’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) and the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS), it is termed Double Materiality.

In a joint statement in September 2023, the GRI and EFRAG (the developers of the ESRS for the European Commission) confirmed the alignment of their respective reporting standards and their approaches to double materiality:

“ESRS and GRI definitions, concepts and disclosures regarding impacts are therefore fully or, when full alignment was not possible due to the content of the CSRD mandate, closely aligned”.

While Double Materiality Assessment is relatively new , organisations that undertake materiality assessment meaningfully should already be considering the effects, impacts and risks that their operations pose to the environment and society through the multiple capitals and resources that they interact with and depend upon. These aspects should already be clearly understood as relevant and of potential ability to affect the company even if they are not included when considered through a narrow “risk-to” / enterprise value lens.

They will very likely be the subject of focus from stakeholders beyond financial actors, and would be identified if a company applies appropriate tests for materiality, such as the Accountability Tests or our questions for assessing materiality noted above.

The bottom line is that if an organisation defines materiality too narrowly, to meet the needs of only one stakeholder (e.g., enterprise value for investors) then they will not escape the need to consider and respond to wider stakeholder requirements which relate to wider impacts upon the planet and society.

Materiality assessment that does not include a consideration of both “risk-to” and “risk from” is not meaningful or likely to drive sustainability.

Salience – what can we learn from human rights?

The United Nations Guiding Principles (UNGP) on Business and Human Rights have a subtly different approach to identifying issues and impacts which a company should consider as priorities – salience.

Salience refers to the quality of importance or prominence. The UNGP highlights the following aspects of salience in order to identify impacts which it contends are frequently missed from conventional materiality approaches, salient impacts are those which are:

- “Most severe: based on how grave and how widespread the impact would be and how hard it would be to put right the resulting harm.

- Potential: meaning those impacts that have some likelihood of occurring in the future, recognizing that these are often, though not limited to, those impacts that have occurred in the past;

- Negative: placing the focus on the avoidance of harm to human rights rather than unrelated initiatives to support or promote human rights;

- Impacts on human rights: placing the focus on risk to people, rather than on risk to the business.”

(Above text from UNGP Salient Human Rights Issues)

Of course, it could be argued that companies which undertake meaningful materiality assessment, and use a risk and stakeholder lens, would be able to identify those human rights issues which UNGP would consider salient. However, the idea of salience reflects a fundamental theme in best practice materiality assessment, that some things are objectively material, no matter how ‘small’ they might appear from some perspectives.

Material when? – future proofing & pushing the materiality envelope

Other challenges for materiality processes in sustainability are timing and timescales. A short-term mindset is more likely to undervalue big picture strategic issues and challenges which operate over years/decades.

Using first principles logic, it’s relatively easy to make the case that sustainability is required for continued operation on a finite planet. However, translating that into priorities for action on a shorter timeframe is more difficult, especially when economics and finance largely do not recognise or reward sustainable behaviours (notwithstanding growing interest in ‘sustainable’ investing – which is largely still investing in the less bad, not absolute good).

Effective materiality assessment therefore means that there should be a focus not just on what is material now, but also what might be material in the future. It is therefore possible to foresee that certain environmental and social trends may give rise to increased costs, risk, reputational damage etc in the future, even though those risks may not be manifest right now.

Therefore, the Accountability 5 Test approach, and our materiality questions, seek to explore a range of reasons why something should be considered as important to manage, some of which, but by no means all, could be measured in direct financial risk and reward terms, but others are recognised and measured through other types of value or risk. The Future Fit Foundation recommend this same type of approach, which they call ‘reverse materiality’.

Reporting 3.0 – Integral Materiality

Another initiative pushing the boundaries of practice in defining what is material is r3.0, a pre-competitive collaboration initiative dedicated to designing and developing blueprint models and management approaches to catalyse the transformation to a regenerative and inclusive global economy.

Reporting 3.0’s Integral Materiality follows a Plan Do Check Act (PDCA) continuous improvement process to support organisations in understanding how their activities relate to vital sources of value (priced and un/under-priced) and the thresholds and limits to sustainable behaviour. In addition, Integral Materiality echoes the approach taken by Social Value International (noted above) to suggest that a move from stakeholders to “rights holders” is required. Rights holders are those ‘to whom companies owe legal duties and ethical obligations due to direct impacts on their wellbeing or, indirect impacts on vital capital resources that these rightsholders rely on for their wellbeing.’ (quote from Medium article linked above).

The focus of these emerging approaches to materiality is on meaningful and contextual sustainability, to locate an organisation approach to sustainable change within the context of planetary limits and thresholds, rather than in the narrow context of an organisation’s own perspective of how sustainability issues might impact them.

See Integral Materiality in its overall context in r3.0’s Blueprint 4: New Business Models (p76). (Note: Terrafiniti is an Advocation Partner of r3.0).

Conclusions

The most forward-looking companies, and those most likely to achieve sustainability, will be ones which treat emerging and future trend risks as material now and therefore develop strategies and plans to mitigate or entirely avoid the challenges they present rather than wait until they are forced to face them.

The advanced and emerging approaches to materiality assessment noted above are most likely to give rise to a future-proofed company, allowing companies to spot and manage issues which may become material in financial, risk and regulatory terms long before they actually ‘bite’.

Like many issues and approaches in sustainability, it can be easy to get confused and lost in a sea of new terms and approaches. However, it is important to understand that materiality is an essential part of meaningful CSR and sustainability management.

In addition, it provides an invaluable means to navigate through complexity, as it presents a way to identify and map issues, develop a clear rationale for prioritisation and allow a logical set of issues for targeting management effort and resources.

Materiality should be at the heart of your sustainability approach.

If it isn’t, you may be missing the point.

DISCOVER MORE | Sustainable Business Strategy

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Worldwide regulators are tightening up on strategic greenwashing to protect consumers, business and market integrity. As further examples arise there is more, we can learn about what regulators will tolerate and what they require of companies.

Put simply, any leeway for general feel-good …

WEF Global Risks 2023 – What’s new and what’s changed?

While big picture environmental threats of climate change, nature loss and ecosystem collapse remain long term risks, geopolitical instability and the current cost-of-living crisis challenges present emerging challenges to the chance for global consensus and coordinated action.

The WEF (World …

2023 sustainable business trends and challenges – what to watch out for

From avoiding greenwashing to facing soaring business costs, 2023 is set to be a challenging year for most business leaders to navigate.

Regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations for good quality, consistent information on sustainability. Communication must be accurate and …

Global Risks 2022

Most major sustainability issues have important risk dimensions for companies – and societies. In many cases these are still not adequately represented in board-level discussion, company risk assessments or registers.

WEF’s Global Risk Report provides a very useful, comprehensive global review and …

Biodiversity – the next crisis?

While we’ve been concerned with action on climate and tied up with Covid19, a larger, related crisis is brewing. Businesses are waking up to the need for action on biodiversity.

Biodiversity is one of many issues organisations should consider when developing (or reviewing) sustainable business …

Transforming the business case for sustainability

In a business context it’s often been necessary to justify why sustainability is important with a business case. While it gets less visibility now, it’s still common to see the symptoms of not having a good business case, or one that’s not widely implemented.

The business case for sustainability – can we make money?

Many people are driven by purpose, the ethical dimension of sustainable business. But all businesses need to make money, we explore where value can be found in sustainable business.

Cost or value? Why is sustainability strategically undervalued?

The business case for sustainability is (shockingly) still either not recognised strategically (i.e. it is understood as an additive factor for operational efficiency or marketing/PR but not as a strategic value creation/destruction factor), or in many cases it is little understood at all.

Sustainability, environmental management and quality – parallels and differences

Sustainability, environmental management and quality – parallels and differences

Leave a Reply