Greenwashing is growing. As the value of making environmental (and social) claims grows, so does bad or poor practice. While this is often unintended, there are significant implications for reputation and trust in responsible communications.

Greenwashing Links – on this page

The meaning of greenwashing | Difference between greenwashing & whitewashing | Where does astroturfing fit in? | Greenwashing or Green Marketing? | Examples of greenwashing | Our Insights | How claims could break consumer law | How to make valid claims | Why Claims can be misleading | The golden age of greenwashing | Greenwashing Terms

As a sustainability & ESG consultancy, we specialise in helping companies and organisations plan and perform more sustainably and help develop more responsible and reliable claims and communication. Our services can help you spot and avoid the risks of greenwashing.

The meaning of greenwashing

Greenwashing is where meaningless or unsubstantiated claims either deliberately or accidentally mislead customers into believing a company’s performance and products are more sustainable than they really are. This can be through claims for environmental performance or outcomes without sufficient context or proof.

Sometimes also called ‘green sheen’, greenwashing can arise through overenthusiasm or from a conscious attempt to mislead or confuse. There is growing awareness of and willingness to respond to global challenges such as climate change and nature loss, which means that both corporate customers and consumers are seeking to be aware of and make informed choices about products and services that have reduced impacts.

Organisations can become overzealous in communications around sustainability, not consciously meaning to mislead but, for instance, publicly setting goals to reduce emissions in unrealistic timeframes.

This, however, is no less harmful to achieving a sustainable future than those actively projecting a smokescreen to distract from the true environmental and social costs of their activities or products. A larger marketing budget is not an indicator of a more sustainable company but it can create more environmental ‘noise’.

The difference between greenwashing and whitewashing

Whereas greenwashing refers to companies falsely claiming environmental benefits or positive environmental contributions, whitewashing is a term used in the event of an individual or organisation deliberately attempting to conceal unpleasant or incriminating facts about themselves or someone they represent.

Where does astroturfing fit in?

Astroturfing (a synthetic surface that mimics grass) is the practice of deliberately masking the promotor of a message, campaign or organisation to make it look like it represents genuine grassroots opinion or support. Often used as a tool for political manipulation, it has been used as a specialist, niche form of greenwashing, especially related to social issues and concerns.

Greenwashing or green marketing?

Green marketing is not necessarily greenwashing. It is perfectly possible to genuinely develop and sell products and services which have reduced relative impacts or other, more positive characteristics.

If described accurately and truthfully then green marketing can avoid the trap of greenwashing. Greenwashing is effectively green marketing done badly – whether from lack of understanding or knowledge – or through a deliberate intention to mislead.

Why is greenwashing increasing?

We think there are a number of reasons – and can identify two major drivers.

Market-led motivations

There are increasing numbers of consumers (and organisations) wanting to purchase products and services that deliver higher (relative) levels of environmental or social performance. This demand is growing and companies see it as a way of gaining differentiation and in many cases also charging a premium for these ‘better’ products.

This driver tends to increase the pressure for the best (most sustainable!) case to be made by brand and marketing functions.

Avoiding change

Few people or organisations really like change and it can be complicated and difficult. Many examples of greenwashing are simply over-extended claims based upon small, incremental changes to products – like including a small quantity of recycled material.

NGOs argue that greenwashing is often used to create the illusion that change is happening when it is not. For high-impact sectors driving significant environmental damage, such activities can act as a distraction or smokescreen for highly unsustainable business as usual.

Recent examples of greenwashing

ASOS, Boohoo and George at Asda

In July 2022, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched an investigation into these three fashion brands with the intent of enforcing the Green Claims Code (GCC). This was done in response to rising complaints about environmental and social claims from companies in the fashion sector.

Ryanair

In 2020, Ryanair advertised that it was the “lowest emissions airline”, prompting the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) to ban the ads, as the claim had no solid evidence to back it up.

Shell

In 2020, the oil and gas company Shell launched a Twitter poll asking ‘What are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?’ The poll went viral, attracting negative critical responses with people pointing out that Shell alone is responsible for around 1-2% of global CO2 emissions per year. It was suggested that this messaging was an attempt to divert public attention away from the company’s most significant impacts. Months after this controversy, Shell was ordered by a European court to reduce their carbon emissions by 45% before 2030 from a baseline of their 2019 emissions.

H&M

With the implementation of “in-store recycling bins”, H&M have encouraged customers to recycle their old clothes for a discount on purchases. However, I:Collect (the company collecting the recycled fabrics) has said that less than 35% of that clothing actually gets properly recycled. The brand has increasingly been the focus of concerns about greenwashing, and is facing a number of lawsuits over its claims and communication on social and environmental issues and performance.

HSBC

In 2022, HSBC bank released adverts relating to their investments in responding to climate change which were found to be misleading by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) when set in the context of their overall investments. HSBC ranks as the UK’s 13th biggest banking financier of fossil fuels, as well as providing funding for thermal coal mining. The ads were subsequently banned after 45 people complained to the ASA.

Our Insights

The Greenwash Files

This page provides updates on notable developments, regulatory action and commentary on what you need to know to reduce your communication risks and concentrate on your valuable message.

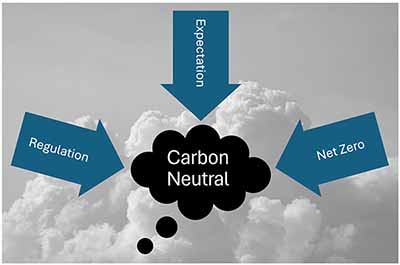

Carbon Neutral Communications

Despite considerable regulatory focus on carbon-neutral claims, companies are still getting their communications wrong, so what is happening?

While many large companies now appear wary of making claims about carbon neutrality, we can still see considerable focus on these in the SME space, some fuelled by questionable labelling schemes.

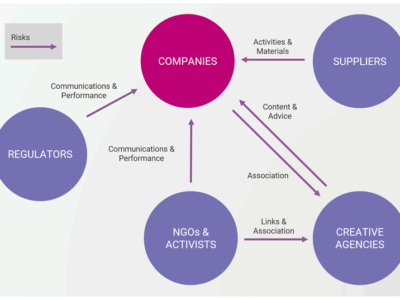

Greenwashing -dimensions of risk

While greenwashing may appear simply irritating, it causes a range of harm and presents multiple business risks. Risks to the company which communicates it – but also risks to companies involved in creating it and those associated with it.

Why your business strategy must be plausible

Regulators are removing leeway for feel-good statements & banning adverts. There are far-reaching implications for responsible strategic communications.

Turning up the heat on green claims

This article highlights and explores the changing regulatory environment for environmental claims and provides insights for ensuring responsible marketing messages.

Why is trust in business important and how greenwashing erodes it

Greenwashing erodes trust and fuels cynicism. Find out more about different types and how to spot them.

How do you best avoid regulatory attention?

Some communications can be seen as misleading, this article assesses environmental claims made by companies, where they can go wrong, and how to make valid claims.

Real Greenwash Kitemark

HUMOUR – our satirical suggestions on how to make sure you really greenwash properly. A fun way of understanding what not to do.

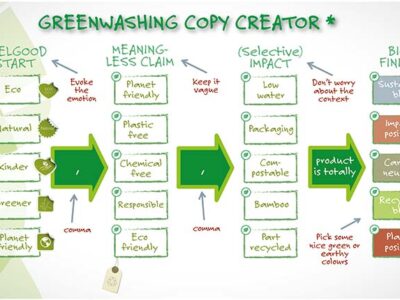

How to create your own greenwash

HUMOUR – more satire! how to easily create copy using the most commonly abused greenwash phrases.

How claims could potentially break consumer law

- Vague assertations

- Unclear or flowery language

- Reference to ‘natural products’ without proper explanation or background

- Deceptive eco logos and labels not associated with legitimate organisations

- Not revealing or explaining relevant information, such as impacts associated with specific products, services or your company

- Not having the right evidence to back up your claims

How to make valid claims

Companies wanting to make a genuine difference and improve the performance of their products and services will want to avoid participating in greenwashing. Whilst it is often the easier route to talk big and do nothing, those who are dedicated to having a positive (or simply a less negative) impact on the environment will need to make sure their claims are clear, accurate, and substantiated with provable facts and figures.

Why claims can be misleading

Claims by companies can be misleading for various reasons: they could be intentionally fraudulent whilst attempting to avoid being found out, or they may be lacking in proper knowledge or expertise.

A Golden Age of Greenwash

This article from Greenpeace explains the origins of greenwashing, how it affects the way companies market to consumers and what that means for the world at large.

Greenwashing terms

No single word, in isolation, is inherently ‘greenwashing’.

However, there are many words and phrases that frequently feature in misleading communications – and are therefore often indicators of possible greenwashing.

While greenwashing is inherently about misleading people, the underlying intent can range from over-enthusiastic but inherently well-motivated marketing (misinformation) to different activities which are actively designed to mislead (misinformation and disinformation).

In this section, we explore the words and phrases that are frequently misused or implicated in greenwashing. We will add further terms/phrases over time…

#1 Natural

Our research so far has revealed that Natural (or associated variations like nature positive, nature’s choice or all natural) is a top 10 greenwashing term.

So, what does it mean?

The short answer is that without some context, it means very little.

Dictionary definition

Looking at the Cambridge Dictionary, the definition of natural is:

“Not artificial”, and

“As found in nature and not involving anything made or done by people”.

This would suggest that natural is not a term that should be used to describe aspects of a product or service, although the Cambridge Dictionary goes on to elaborate:

“Natural food or drink is pure and has no chemical substances added to it and is therefore thought to be healthy”.

Now we’re starting to unpack the power of the word and some of the meaning and association that its use is often trying to invoke.

There are perhaps two main aspects:

a. Safety – to seek to imply that a natural product (or a product containing ‘natural’ elements) is inherently safe and pure.

b. Proximity to nature (and hence distance from artificiality) that is implied to be inherently ‘good’.

Neither of these is necessarily true.

Many ‘natural’ things are particularly poisonous or hazardous. For example, Death Caps, Deadly Nightshade, cyanide, arsenic, radioactivity and volcanoes are all natural – and all potentially deadly.

Synthetic compounds or artificial products are not necessarily toxic or dangerous either.

Avoiding toxicity requires systematic scientific investigation and knowledge.

The popularity of natural medicines or treatments, in part derives from the notion that they are inherently safer than conventional treatments – which of course is also potentially false. If they are effective and a dose/response relationship can be demonstrated, then it’s likely due to active compounds that could also have negative effects in overdose. Treatment which is believed to be effective when it is not can also be damaging.

Similar logic is applied to ‘natural’ products. They are meant to imply the product is less damaging to people or the environment than alternatives.

There can be some truth to this. Less unsustainable products potentially come from more ‘natural’ resources or feedstocks – but they are not inherently better. Understanding the context and supply chain impacts is vital to make informed choices.

Natural products that have significant sustainability impacts include for example:

- Peat (habitat loss and huge carbon emissions)

- Timber not sourced from crops (habitat degradation and loss)

- Wild harvested animals or plants (species loss)

- Cotton (land use impacts, pesticide pollution, child labour).

In conclusion, the term natural, as applied to products or services, is effectively meaningless without more detailed information about safety, toxicology, environmental and social impacts.

In the UK, while the Green Claims code (and equivalents in other countries) does not single out ‘natural’ it’s likely that reliance upon it without supporting information could trigger multiple clauses – including #3:

“The claim clearly tells the whole story of a product or service; or relates to one part of the product or service without misleading people about the other parts or the overall impact on the environment.”

What is a socially responsible advert?

On the 22nd of November 2023 the UK’s Advertising Standards Agency (ASA) banned an advert on environmental grounds.

But that’s not unusual you ask?

No, perhaps not, but it looks like there’s an interesting aspect to this latest case.

The posters and videos were adverts for Toyota Hilux off-road pick-ups. The ads have been banned for promoting or condoning driving that disregards environmental impacts. In what appears to be a possible landmark ruling, this is the first time that the ASA has blocked an advert for breaching social responsibility.

The video for the advert mimics a nature documentary and shows a large group of Hilux cars crossing a wild landscape and driving through a river, the voiceover stating, “one of nature’s true spectacles”.

A complaint to the ASA was made by the pressure groups Adfree Cities and Badvertising. They have both called for advertising promoting high-carbon products and services to end.

Toyota justified the campaign by arguing that people in certain industries, such as farming and forestry, needed such tough capable vehicles. However, these roles were not depicted in the adverts which went on to depict the vehicles in urban environments.

What’s the environmental background to this?

While offroad driving is highly restricted in the UK, the footage (some of which was apparently CGI) did depict arguably damaging activity. However, the greater issue is the promotion of larger, heavier and more polluting cars to the wider population.

Climate group Possible has calculated that the popularity of SUV means that the average ICE car in 2023 has higher carbon emissions than the average 10 years ago – that effectively the increase in average car size has cancelled out improvements in fuel efficiency.

What are the further implications?

Many of the previous adverts that have been banned on environmental grounds have related to various types of misdirection or claims that can not be adequately substantiated.

In this case, the ASA stated that the ads:

“condoned the use of vehicles in a manner that disregarded their impact on nature and the environment … they had not been prepared with a sense of responsibility to society”.

This ruling is on a different basis from many other rulings involving environmental claims. CAP Code 1.3 states that “Marketing communications must be prepared with a sense of responsibility to consumers and to society.” The ASA has stated that wider social responsibility is an area it thinks will require greater scrutiny in the future.

Can we help you?

We’ve worked with companies in the UK, Europe and

beyond to avoid greenwash by developing responsible communications approaches, content and copy. Ranging from strategic corporate reporting and disclosure to brand guidelines or in-store packs, we can help you develop content that’s clear, accurate and substantiated.

Book a chat with one of our partners to explore how we might help you – there’s no obligation!