Will 2020 bring real climate action?

The second in our series on the big sustainability issues for 2020, what will be the focus on climate in 2020?

2019 was notable for its focus on climate. Perhaps at least partly due to Greta Thunberg’s persistence, global reach and profile and related, global rise of the school strikes movement, highlighting the generational pressure to respond to the threat to Children’s futures.

Climate will remain perhaps the most vital sustainability issue of 2020, but the crucial question is, will attention finally convert into meaningful and proportionate action?

The 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change required all signatories (almost every country on earth) to avoid dangerous climate change, it also articulated the need to find equitable ways to reduce global greenhouse gas emissions.

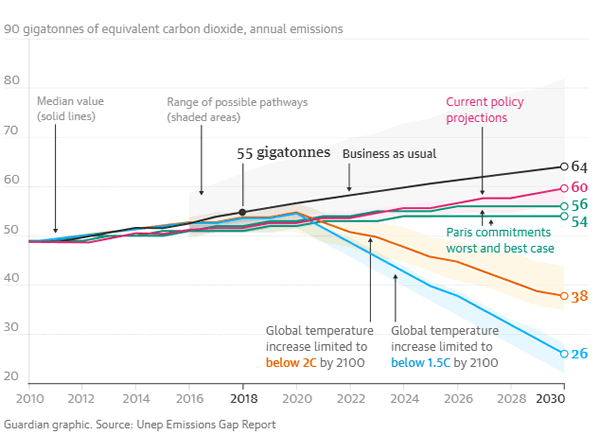

If we rely only on the current climate commitments of the Paris Agreement, temperatures can be expected to rise to 3.2°C this century. Temperatures have already increased 1.1°C, leaving families, homes and communities devastated.

UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2019 – www.unenvironment.org/interactive/emissions-gap-report/2019/

At face value, Europe has done well on reducing emissions, but this masks a wider problem. Since 1990 global atmospheric CO2 concentrations have increased every year, last year reaching 2.7ppm.

China is still the largest emitter, producing nearly twice its nearest rival. The USA, EU and India remain major polluters contributing to over 55% of total emissions. These rankings do not include land-use change related emissions – if they did, Brazil could be the largest emitter for forest loss.

So why is there still a global increase? It is important to consider the import of emissions. China is largely the greatest emitter because in Europe, and elsewhere, we have effectively outsourced manufacturing there. So, despite having carbon polices and apparently falling emissions, Europe is not improving overall performance as we’re importing emissions from China.

The European Commission has recognised the need for carbon border taxes on imports to deal with this issue, but the proposal is some years away from becoming reality.

Madrid, COP 25

COP25 (the 25th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change) was the longest on record, overrunning its schedule by 42 hours. Aiming to agree the rulebook for the earlier Paris Agreement, it was also meant to represent a statement of intent to take action.

Yet again this failed to materialise, with many decisions being further deferred to 2020.

Throughout the talks one the major areas of disagreement was around the need to agree accounting rules for the Paris Agreement’s Article 6 and the attempts to remove double-counting, an issue highlighted by Greta Thunberg.

Article 6 provides for a global market in carbon and is intended to allow richer countries to meet targets by buying credits that fund reductions in developing countries. Even if the problems are resolved and workable solution is found, offsets remain controversial because the absolute emissions cuts needed to meet science-based targets are of a greater scale and require immediate action.

(graphic the Guardian https://www.theguardian.com/news/2019/dec/02/climate-crisis-what-is-cop-and-can-it-save-the-world)

Metrics continue to pose a problem. They provide an accounting means to convert other global warming emissions (such as methane and nitrous oxide) into a common measure expressed in terms of CO2. The metrics now in use for the Paris Agreement are different to those under the climate convention. Developed and developing countries use different global warming values for reporting emissions – as common methods were not agreed at COP 25, the negotiations have been deferred to 2020.

Where next for global agreements?

Will 2020 be the climate crunch year? The remaining sticking points will carry over to November 2020’s COP in Glasgow, some may be dealt with in the interim meeting in Bonn. The Glasgow meeting is intended to herald the implementation of the Paris agreement.

The biggest question is, with a history of non-achievement, is the COP process fit for purpose? If we keep trying the same thing will we get the same results? The problem is, it is all we have, and international collaboration is essential to deal with a global crisis.

Somehow, we just have to find a way to make it work. But hope is not a strategy.

To meet the objectives set at Paris, national targets must be more ambitious still and the deadline is 2020. But we need to go further, beyond Paris agreements, to even approach 2 or even 1.5 degree ambitions.

With climate disruption manifesting as more extreme, faster moving and more unpredictable with every passing year, such failures in international governance look more and more like fiddling while Rome (or Australia) burns.

DISCOVER MORE | Sustainability Issues

Coffee ads banned for misleading ‘compostable’ claims

Two major coffee brands, Lavazza and Dualit, have had their adverts banned by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) for making misleading claims that their coffee pods and bags were ‘compostable’.

The ASA found that both companies gave the false impression that these products could be …

Carbon Neutral Communications

Despite considerable regulatory focus on carbon neutral claims, companies are still getting their communications wrong, so what is happening?

While many large companies now appear wary of making claims about carbon neutrality, we can still see considerable focus on these in the SME space, some …

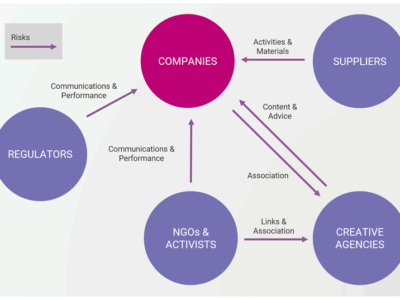

Reputation risk and sustainability – who do you work with?

Reputation is widely regarded as one the most valuable assets of an organisation. Sustainability can also be an important contributor to both reputation and several dimensions of business value.

In this article we explore different dimensions of reputational risk, how it might be affected and how …

Sustainable Aviation?

On the 28 November 2023, the first long-haul passenger plane powered with ‘sustainable’ air fuel took off. SAF offers an ostensibly attractive path for decarbonisation for the airline industry – the lifecycle greenhouse emissions can be up to 70% lower than conventional fossil-based fuels.

While …

Greenwashing – dimensions of risk

Greenwashing – misleading communications on sustainability issues – has various dimensions of risk, but these are often overlooked, and their implications are insufficiently examined.

While greenwashing may appear as simply irritating, it actually causes a range of harm and presents multiple …

Sustainable transition – waiting for the underpants gnomes?

Dramatic changes are needed in business and industry to head off coming poly crises and build a prosperous future for the growing global population.

But plans for this ‘sustainable transition’ are few and far between and often lack credible substance to bridge the link between ambition and action. …

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Worldwide regulators are tightening up on strategic greenwashing to protect consumers, business and market integrity. As further examples arise there is more, we can learn about what regulators will tolerate and what they require of companies.

Put simply, any leeway for general feel-good …

WEF Global Risks 2023 – What’s new and what’s changed?

While big picture environmental threats of climate change, nature loss and ecosystem collapse remain long term risks, geopolitical instability and the current cost-of-living crisis challenges present emerging challenges to the chance for global consensus and coordinated action.

The WEF (World …

2023 sustainable business trends and challenges – what to watch out for

From avoiding greenwashing to facing soaring business costs, 2023 is set to be a challenging year for most business leaders to navigate.

Regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations for good quality, consistent information on sustainability. Communication must be accurate and …

Sustainable value creation

Understanding the relationship between your organisation and the wider world, and identifying which issues, trends, dependencies and risks are material (important) to your business future is critical. Not just for measuring and managing impact, but also for developing resilience and responding to …

Is your organisation responding to climate issues? Contact me to discuss what you could improve.

Contact Dominic

2020 Sustainability Issues

2020 Sustainability Issues

Leave a Reply