How far you can go without destroying from within what you are trying to defend from without?

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Diesel air pollution is a global issue that has received particular focus here in the UK in recent months. Scrutiny has increased following the VW emissions scandal and ongoing research that has increased understanding into the health impacts of diesel air pollution. Air pollution can damage us at all stages of life from before birth to old age, it contributes to chronic conditions including heart disease, cancer, asthma and dementia (NHS). The recent Royal College of Physicians report suggested that air pollution cases up to 40,000 annual premature deaths in the UK.

But this is of course a worldwide phenomenon, the mayors of Athens, Madrid, Mexico City and Paris are also planning to ban diesel vehicles from their cities by 2025.

As always with anything that costs or makes people money there’s a lot of confusion around the issue of diesel air pollution wafting around. How do we try and navigate the issues here?

Diesel air pollution – clearing the air

Burning diesel contributes to pollution (although it’s not the only source) in three main ways:

Particulates – small particles of solid material that become airborne. These arise from a range of sources including agriculture, mining, industrial process and transport. Vehicles generate particulates from combustion and also generate particles from tyre and brake wear. Diesel engines generate more particulates than petrol ones. Particulates are classified according to their size, the main transport-related sizes are PM 2.5 and PM 10 (up to 2.5/10 micrometers respectively). The smaller particles have the greatest health impacts affecting the cardiovascular system and lung function.

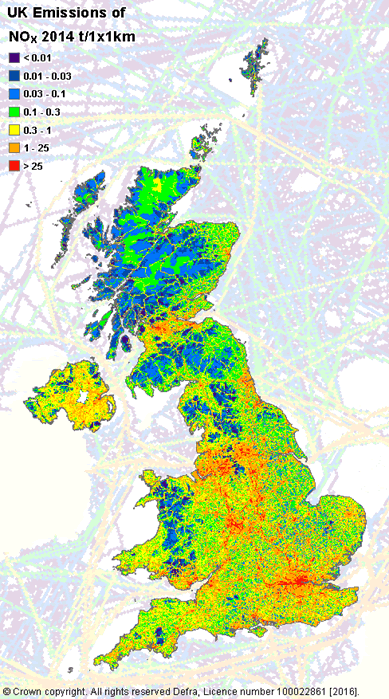

Noxious NOx – in air pollution terms, collectively refers to Nitrogen Oxide (NO) and Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2) – both oxides of Nitrogen (NOx). NOx reacts with water or ammonia to form Nitric acid which can damage lung tissue. In the presence of sunlight, NOx reacts with volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to form and in some situations, destroy ozone. In the UK road transport accounts for c.34% of NOx emissions and these were the main focus of the Volkswagen emission violations.

Ozone – high up in the atmosphere ozone (O3) is useful stuff, filtering out large amounts of ultraviolet radiation. However, ozone is a powerful oxidising agent and near ground level ozone can damage mucous and respiratory tissue and harm lung function.

Vehicle Emissions standards

Love or loathe the EU, it has been at the forefront of setting emissions standards for vehicles, but as we now know these have been problematic on several levels. The regulatory framework has a relatively straightforward logic – set increasingly stringent standards that manufacturers must meet. This has resulted in the evolution of different Euro standards (1 – 6) over time with the focus for Euro 6 to converge NOx and particulate emissions for diesel and petrol engines. The corresponding standards for larger commercial vehicles (lorries, buses etc.) have been more stringent for several years.

European emission standards for passenger cars, g/km

| TIER | DATE | CO | NOx | HC + NOx | PM | PN [#/km] |

| Diesel | ||||||

| Euro 1 | July 1992 | 2.72 | – | 0.97 | 0.14 | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1996 | 1.0 | – | 0.7 | 0.08 | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | 0.66 | 0.50 | 0.56 | 0.05 | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.025 | – |

| Euro 5a | September 2009 | 0.50 | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.005 | – |

| Euro 5b | September 2011 | 0.50 | 0.180 | 0.230 | 0.005 | 6×1011 |

| Euro 6 | September 2014 | 0.50 | 0.080 | 0.170 | 0.005 | 6×1011 |

| Petrol | ||||||

| Euro 1 | July 1992 | 2.72 | – | 0.97 | – | – |

| Euro 2 | January 1996 | 2.2 | – | 0.5 | – | – |

| Euro 3 | January 2000 | 2.3 | 0.15 | – | – | – |

| Euro 4 | January 2005 | 1.0 | 0.08 | – | – | – |

| Euro 5 | September 2009 | 1.0 | 0.060 | – | 0.005 | – |

| Euro 6 | September 2014 | 1.0 | 0.060 | – | 0.005 | 6×1011 |

| CO | Carbon Monoxide | |||||

| NOx | Nitrogen Oxides | |||||

| HC + NOx | Hydrocarbons & NOx | |||||

| PM | Particulate Matter | |||||

| PN | Particle Number |

The standards are tested and enforced in a standard and what is intended to be fair process. Currently all cars sold in the UK are subject to New European Driving Cycle (NEDC) procedure. This involves testing in laboratory conditions on a rolling road. Cars to be tested are randomly selected from production lines by the testing authorities and tests are conducted under standardised conditions to allow comparisons between vehicles.

Where have these gone wrong?

In two key ways. Firstly, while the tests provide some basis for comparison they do not reflect real world performance which in most cases is far worse than the lab tests. This is likely due to several reasons including:

- differences in test conditions – including driving up and down hills, in heavy traffic, in different temperatures, weather conditions and distances.

- targeting – taxation in Europe has largely been focused on CO2, manufacturers have been optimising for this rather than fuel consumption or other emissions.

Secondly, it’s clear from the VW scandal that at least one major manufacturer has deliberately circumvented the tests. While VW Group finally admitted their software fix to defeat the testing cycles, many other makers are coming under the spotlight for exploiting loopholes in the testing procedures. Transport & Environment has conducted research into diesel emissions levels, including publishing their ‘dirty thirty’ list. This is based upon investigations conducted in Germany, France and the UK and included vehicles which:

- Were ‘Euro 6’ (latest EU emission class) models;

- had NOx emissions over 400 mg/km (5 times the Euro 6 NOx limit of 80 mg/km) for RDE (Real World Driving) test results;

- had NOx emissions over 160 mg/km (2 times the Euro 6 limit) in NEDS tests;

- included a wide selection of manufacturers to illustrate the greatest spectrum of emissions problems.

The full list of polluting vehicles is available here.

Transport & Environment identified three key areas that defeat devices target:

- Thermal windows – switching off or weakening exhaust treatment systems at temperatures below those typically used for lab tests;

- Hot restarts – test data showed (23/30 cars) higher emissions after a hot start compared to a cold one. Suggesting different engine calibration is used for cold starts (as are used in EU tests);

- Cycle detection – EU tests take 19 minutes, German testing authorities have found one manufacturer’s exhaust treatment system turning off after 20 minutes.

Research by the consumer group Which? examined 278 diesel cars manufactured 2012 – 2016, testing average NOx emissions compared to Euro 5 (0.18g/km) and Euro 6 (0.08g/km) limits. They found emissions levels up to 400% higher than regulations required for Euro 5 (0.73g/km) and 900% above (0.72g/km) Euro 6 levels.

There are a variety of possible reasons for the gap between test and real world performance, but the additions by VW and the emerging evidence on other manufacturers points to avoidance measures. Automotive News refers to a range of “euphemisms such as “engine calibration,” “acoustic function,” “thermal window” — or in the U.S., “auxiliary emissions control devices” — describe conditions under which car makers may minimize or switch off their expensive exhaust-treatment systems in the name of guaranteeing mechanical durability”.

They also report on investigations by German authorities which suggest widespread use of these largely legal devices. Why are they apparently legal? Manufacturers have negotiated a range of exemptions and mitigations to allow emissions management to be turned off ostensibly to prolong engine life or for safety reasons. However, in Europe they do not have to declare if they have employed these features (they do under the US regulatory framework).

Crisis in trust … and in action

An article in the influential journal Nature in May 2017, suggested that worldwide there were 38,000 excess annual deaths related to the failure of diesel vehicles to meet regulated limits in real world conditions. The majority of these deaths are concentrated in Europe where diesel cars are relatively common and India and China where dirty trucks and vans are more prevalent. If all vehicles met the current regulatory limits worldwide the study calculated NOx emissions could still account for 70,000 annual excess deaths worldwide.

The situation has resulted in a crisis of trust, car manufacturers are distrusted by both regulators and the public. The EU Real Driving Emissions (RDE) regulations may at last offer a more thorough and realistic regulatory framework and thereby at least a more transparent and level playing field for manufacturers, these begin to apply in September 2017 for new type approvals and September 2018 for all new vehicles. But even if this new paradigm is successful what about the current ‘fleet’. In the UK there are c. 12M diesel vehicles in use that passed through the previous shaky regulatory regime and are currently doing all of us harm whether we drive them or not.

The UK Government has been repeatedly chastised in the courts for its failure to get a grip on air quality. As a result new plans are under consultation, these include possible:

- ‘toxin taxes’ to enter restricted urban areas

- bans on diesel cars in city centres – maybe related to emissions standards – i.e. below Euro 6

- rises in VED tax in 2017 Autumn budget

- Clean Air Zone establishment and expansion by local authorities

- vehicle scrappage or retro-fitting schemes to be handled by local authorities.

While the current plans are under consideration, it appears that additional ‘toxin taxes’ could apply in at least 27 UK cities for motorists bringing in diesel cars and some local authorities in London already charge higher rates for parking for ‘dirtier’ vehicles.

Driving forward?

Like many issues in sustainability, diesel pollution is a complex mixture of responsibility, governance, regulation, politics, and technology. It is also a ‘commons’ issue because we are all affected by air quality and because the parties that give rise to the impacts aren’t necessarily those which bear the costs.

The drive towards diesel in the UK was encouraged by the taxation structure provided by Gordon Brown in 1998 as Chancellor of the Exchequer. It was promoted as part of a push to lower CO2 emissions and reflected similar initiatives across Europe, but failed to encompass the wider issues and has had a range of unforeseen consequences. This previous signal to consumers to purchase diesel vehicles means that government bears considerable responsibility in sorting it out. People bought diesel in good faith, believing that it was a relatively clean choice, a position also promoted by the motoring press. Consequently, politicians are hesitant to ban or punitively tax the use of diesel vehicles. Many commentators believe the Government’s emphasis in the current policy consultation on action via local authorities is a failure in leadership.

So what would an adequate and reasonably equitable response look like? Much of the discussion revolves around cost, be it the personal costs to an individual to purchase an alternative vehicle or the costs to national or local government to fund scrappage schemes, or the costs to the community in ill-health, loss of productivity, increased health costs and shortened lives.

Taken objectively the societal ‘cost’ of 40,000 excess annual deaths is extraordinary and that’s not even including the moral consideration for action. Like trying to dislodge any established technology, change will be difficult, controversial and expensive – but nothing like the price of inaction.

DISCOVER MORE | Sustainability Issues

Coffee ads banned for misleading ‘compostable’ claims

Two major coffee brands, Lavazza and Dualit, have had their adverts banned by the UK’s Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) for making misleading claims that their coffee pods and bags were ‘compostable’.

The ASA found that both companies gave the false impression that these products could be …

Carbon Neutral Communications

Despite considerable regulatory focus on carbon neutral claims, companies are still getting their communications wrong, so what is happening?

While many large companies now appear wary of making claims about carbon neutrality, we can still see considerable focus on these in the SME space, some …

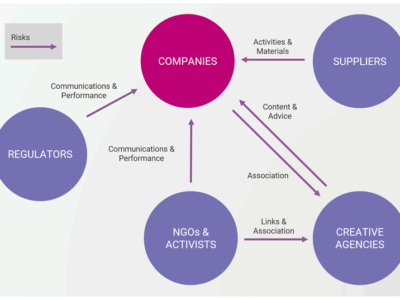

Reputation risk and sustainability – who do you work with?

Reputation is widely regarded as one the most valuable assets of an organisation. Sustainability can also be an important contributor to both reputation and several dimensions of business value.

In this article we explore different dimensions of reputational risk, how it might be affected and how …

Sustainable Aviation?

On the 28 November 2023, the first long-haul passenger plane powered with ‘sustainable’ air fuel took off. SAF offers an ostensibly attractive path for decarbonisation for the airline industry – the lifecycle greenhouse emissions can be up to 70% lower than conventional fossil-based fuels.

While …

Greenwashing – dimensions of risk

Greenwashing – misleading communications on sustainability issues – has various dimensions of risk, but these are often overlooked, and their implications are insufficiently examined.

While greenwashing may appear as simply irritating, it actually causes a range of harm and presents multiple …

Sustainable transition – waiting for the underpants gnomes?

Dramatic changes are needed in business and industry to head off coming poly crises and build a prosperous future for the growing global population.

But plans for this ‘sustainable transition’ are few and far between and often lack credible substance to bridge the link between ambition and action. …

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – why your business strategy must be plausible

Worldwide regulators are tightening up on strategic greenwashing to protect consumers, business and market integrity. As further examples arise there is more, we can learn about what regulators will tolerate and what they require of companies.

Put simply, any leeway for general feel-good …

WEF Global Risks 2023 – What’s new and what’s changed?

While big picture environmental threats of climate change, nature loss and ecosystem collapse remain long term risks, geopolitical instability and the current cost-of-living crisis challenges present emerging challenges to the chance for global consensus and coordinated action.

The WEF (World …

2023 sustainable business trends and challenges – what to watch out for

From avoiding greenwashing to facing soaring business costs, 2023 is set to be a challenging year for most business leaders to navigate.

Regulators, customers and consumers have increasing expectations for good quality, consistent information on sustainability. Communication must be accurate and …

Sustainable value creation

Understanding the relationship between your organisation and the wider world, and identifying which issues, trends, dependencies and risks are material (important) to your business future is critical. Not just for measuring and managing impact, but also for developing resilience and responding to …

Fossil fuels used in the vehicles are the main source of air pollution and it will affects us in both direct and indirect way. So, suitable initiatives should be taken to reduce the emission of such hazardous gases. Use of EV or development of a hydrogen fuel cell for vehicles could be the best alternative way to minimize the emission of such poisonous gases. The threat of air pollution of very real and without proper initiatives, it’s effects could be very devastating.