Greenwashing is growing. As the value of making environmental (and social) claims grows, so does bad or poor practice. While this is often unintended, there are significant implications for reputation and trust in responsible communications.

Greenwashing Links – on this page

The meaning of greenwashing | Difference between greenwashing & whitewashing | What is Greenhushing? | Where does astroturfing fit in? | Greenwashing or Green Marketing? | Examples of greenwashing | Our Insights | How claims could break consumer law | How to make valid claims | Why Claims can be misleading | The golden age of greenwashing | Greenwashing Terms

As a sustainability & ESG consultancy, we specialise in helping companies and organisations plan and perform more sustainably and help develop more responsible and reliable claims and communication. Our services can help you spot and avoid the risks of greenwashing.

The meaning of greenwashing

Greenwashing is where meaningless or unsubstantiated claims either deliberately or accidentally mislead customers into believing a company’s performance and products are more sustainable than they really are. This can be through claims for environmental performance or outcomes without sufficient context or proof.

Sometimes also called ‘green sheen’, greenwashing can arise through overenthusiasm or from a conscious attempt to mislead or confuse. There is growing awareness of and willingness to respond to global challenges such as climate change and nature loss, which means that both corporate customers and consumers are seeking to be aware of and make informed choices about products and services that have reduced impacts.

Organisations can become overzealous in communications around sustainability, not consciously meaning to mislead but, for instance, publicly setting goals to reduce emissions in unrealistic timeframes; in this way, greenwashing representation can harm businesses in ways they can’t foresee.

This is no less harmful to achieving a sustainable future than those actively projecting a smokescreen to distract from the true environmental and social costs of their activities or products. A larger marketing budget is not an indicator of a more sustainable company but it can create more environmental ‘noise’.

The difference between greenwashing and whitewashing

Where greenwashing refers to companies falsely claiming environmental benefits or positive environmental contributions, whitewashing is a term used in the event of an individual or organisation deliberately attempting to conceal unpleasant or incriminating facts about themselves or someone they represent. It’s important to draw a distinction between these two terms, lest we begin to attribute blame for the wrong reasons.

Greenhushing

Greenhushing refers to the practice of deliberately downplaying or withholding information about a company’s sustainability initiatives. This is often done to avoid attracting criticism, political controversy, or accusations of greenwashing that could harm the company’s reputation. Stakeholders such as customers and investors may raise concerns or even trigger legal challenges. In some cases, businesses may also believe their environmental efforts are too minor to promote, or they may prefer to wait until they have more meaningful progress to report.

Where does astroturfing fit in?

Astroturfing (a synthetic surface that mimics grass) is the practice of deliberately masking the promotor of a message, campaign or organisation to make it look like it represents genuine grassroots opinion or support. Often used as a tool for political manipulation, it has been used as a specialist, niche form of greenwashing, especially related to social issues and concerns.

Greenwashing or green marketing?

Green marketing is not necessarily greenwashing. It is perfectly possible to genuinely develop and sell products and services which have reduced relative impacts or other, more positive characteristics.

If described accurately and truthfully then green marketing can avoid the trap of greenwashing. Greenwashing is effectively green marketing done badly – whether from lack of understanding or knowledge – or through a deliberate intention to mislead.

Why is greenwashing increasing?

We think there are a number of reasons – and can identify two major drivers.

Market-led motivations

There are increasing numbers of consumers (and organisations) wanting to purchase products and services that deliver higher (relative) levels of environmental or social performance. This demand is growing and companies see it as a way of gaining differentiation and in many cases also charging a premium for these ‘better’ products.

This driver tends to increase the pressure for the best (most sustainable!) case to be made by brand and marketing functions.

Avoiding change

Few people or organisations really like change and it can be complicated and difficult. Many examples of greenwashing are simply over-extended claims based upon small, incremental changes to products – like including a small quantity of recycled material.

NGOs argue that greenwashing is often used to create the illusion that change is happening when it is not. For high-impact sectors driving significant environmental damage, such activities can act as a distraction or smokescreen for highly unsustainable business as usual.

Recent examples of greenwashing

Nike, Superdry and Lacoste ads banned

Claims that products are sustainable are not difficult to find. If you are familiar with good practice in responsible green communications and/or the Green Claims Code, you’ll know that making such an ‘absolute’ claim sets a high bar for substantiation of that claim. Absolute claims require comprehensive, high-quality evidence to back them up which should apply to the entire lifecycle of the product unless partial relevance is very clearly stated.

In practice this means that absolute or general claims are high risk and should generally be avoided. In practice of course, companies still make absolute claims – as is the case in the examples described here – with the result that ads were banned.

The Superdry Google ad, stating “Superdry: Sustainable Style. Unlock a wardrobe that combines style and sustainability […]” was found to fall short on clarity, meaning and available evidence.

The Nike Google ad stated, “Nike Tennis Polo Shirts – Serve An Ace With Nike […] Sustainable Materials”. This was found to be misleading because the basis and meaning of the claim ‘sustainable materials’ had not been made clear and lacked evidence to support it.

Interestingly, Nike claimed sustainability based on using recycled polyester materials in the product and referred to an industry tool (Higg MSI) showing the environmental impact of using recycled polyester and a relative reduction in carbon impacts compared to virgin materials. Nike considered this an environmental benefit. The UK ASA (Advertising Standards Authority) considers that a product described as ‘sustainable’ should at the least have no detrimental impact on the environment, and this was not demonstrated by Nike.

We can see an emerging pattern here, the Lacoste ad stated, “Lacoste Kids – Sustainable […] clothing”. When challenged by the ASA, Lacoste provided information which did show a reduction in environmental footprint across the main life cycle stages of their SS25 Kids collection – compared to 2022. However, the ASA’s assessment considered that: “Lacoste had not provided evidence to demonstrate that their products had no detrimental effect on the environment, taking into account their entire life cycle.” – a threshold implied by the use of an absolute claim of performance like “sustainable clothing”.

So, what if anything has changed here, and what can we learn?

It’s no coincidence that these three similar ads/claims received rulings at the same time (03-12-2025). The ASA (as well as the CMA – UK Competition and Markets Authority) has been doing wider work investigating environmental claims in the retail fashion sector.

Both the ASA and the CMA have said that they use AI systems to proactively identify non-compliant communications. In these cases, the ASA used their Active Ad Monitoring system. The lesson here is that companies run a real and active risk of regulatory action and reputational impacts for inaccurate and misleading sustainability related messaging.

Perhaps the end of the era of companies blithely claiming that their products are sustainable is in sight.

ASOS, Boohoo and George at Asda

In July 2022, the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) launched an investigation into these three fashion brands with the intent of enforcing the Green Claims Code (GCC). This was done in response to rising complaints about environmental and social claims from companies in the fashion sector.

Ryanair

In 2020, Ryanair advertised that it was the “lowest emissions airline”, prompting the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) to ban the ads, as the claim had no solid evidence to back it up.

Shell

In 2020, the oil and gas company Shell launched a Twitter poll asking ‘What are you willing to change to help reduce emissions?’ The poll went viral, attracting negative critical responses with people pointing out that Shell alone is responsible for around 1-2% of global CO2 emissions per year. It was suggested that this messaging was an attempt to divert public attention away from the company’s most significant impacts. Months after this controversy, Shell was ordered by a European court to reduce their carbon emissions by 45% before 2030 from a baseline of their 2019 emissions.

H&M

With the implementation of “in-store recycling bins”, H&M have encouraged customers to recycle their old clothes for a discount on purchases. However, I:Collect (the company collecting the recycled fabrics) has said that less than 35% of that clothing actually gets properly recycled. The brand has increasingly been the focus of concerns about greenwashing, and is facing a number of lawsuits over its claims and communication on social and environmental issues and performance.

HSBC

In 2022, HSBC bank released adverts relating to their investments in responding to climate change which were found to be misleading by the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) when set in the context of their overall investments. HSBC ranks as the UK’s 13th biggest banking financier of fossil fuels, as well as providing funding for thermal coal mining. The ads were subsequently banned after 45 people complained to the ASA.

Our Insights

- Why Greenwashing Matters and How to Avoid It

- Real Greenwash KitemarkTM

- Greenwashing: Dimensions of Risk

- Avoiding Strategic Greenwashing and Establishing Plausibility

- Failing Standards & Facilitating Greenwashing: The Greenwash Files

- Turning Up the Heat on Green Claims

- Carbon Neutral Communications

- New Tab

The need for meaningful change in business practice to deliver sustainability and equity is perhaps more pressing than ever. But persistent greenwashing undermines the wider understanding of sustainability, erodes trust, adds confusion and fuels cynicism.

“I’m not upset that you lied to me, I’m upset that from now on I can’t believe you.”

Friedrich Nietzsche

Greenwashing – undermining trust

The COVID-19 crisis has added momentum to the need for us to be able to trust who we buy from and what we buy.

Nielsen’s recent report Recalibrated consumption dynamics in a Covid-19 altered world noted that “Authenticity, trust and empathy have been the winning traits of those brands that remained ‘on air’ and relevant to consumers emerging needs”.

Edelman’s annual Trust Barometer Survey echoes and underlines this view. The 2020 Report found that overall, trust in our institutions is decreasing. But that people are increasingly looking for leadership from business to engage in and tackle social and environmental issues.

Given these findings, companies need to prove they are capable of being trusted. Central to their trustworthiness is firstly, the way that they make and justify claims about sustainability progress, and secondly, the characteristics and performance of their products.

There are two important aspects here.

Firstly, corporate statements of commitment and intent (often included in corporate sustainability or CSR reports); and

Secondly product-level claims. They are very different, and it is the latter that we focus on here.

However, the extent to which we should rely upon, and be able to trust statements in corporate sustainability reports and disclosures is also an essential component of meaningful sustainability.

Greenwashing at the product-level: feel good or feel true?

How can you know whether a statement, or message relating to the sustainability of a product, is true? This is the question at the heart of greenwashing.

Greenwashing is a term coined in a 1986 essay by the environmentalist Jay Westerveld, in which he claimed the hotel industry falsely promoted the reuse of towels as part of a broader environmental strategy. In fact, the act was designed as a cost-saving measure.

While it can legitimately (perhaps) be argued that the outcomes are just as important as the intent, greenwashing refers to a fundamental challenge – are the claims made for products and activities true and meaningful in the context of reduced environmental and social impact or product benefits? Or are they merely marketing or PR with no substance?

Greenwashing means that a claim is either not true, not relevant or intended to actively mislead the recipient as to the actual performance or characteristics of a product.

Spotting greenwash

But just what does greenwash look like? If you see any of the following terms or phrases in corporate communications or on product packaging, you are likely to be experiencing greenwashing:

- “All our operations are environmentally friendly”

- “Green”

- “Nature’s choice”

- “100% Sustainable”

- “Climate-friendly”

- “All natural”

- “People and planet in harmony”

What makes them greenwash? The simple answer is that none of them really mean anything or can be proved or justified.

The longer answer is that they lack context, legitimacy and comparability. In 2007 the characteristics and elements of greenwashing were characterised as the “Seven Sins of Greenwashing” by TerraChoice (now part of UL, see here).

The 7 sins are all forms of dissembling – either outright mistruths, or half/part truths intended to convey an impression that cannot be justified.

Types of greenwash

So what are the fundamental aspects you can use to assess and identify greenwash?

1. Just plain lying

This can take different forms, like claiming standards or certifications which have not been earned or falsifying audit documentation to support this. Often certified goods or materials command higher prices, so if you can ‘certify’ a shipment of cocoa/cotton/coffee to an environmental standard by fiddling the paperwork, you can make an instant profit.

One of the most prominent recent examples would be Volkswagen’s emission cheating program. The car-maker fitted vehicles with software to cheat emissions testing programs – thereby enabling dirty vehicles that were not compliant to pass regulatory tests.

Another example of just plain lying would be to refer to or include a product label that doesn’t exist, or one that doesn’t actually require any sustainable change.

2. Misdirection

Most greenwash claims are focused on different forms of misdirection. It’s a separate category because some of these forms could be construed as making some valid (i.e. true claims) from a position of partial ignorance. Overall, the result is misdirection and untruth, but the motive can be less clear.

What does this look like?

Typically, being selective about specific aspects of origin or performance or characteristics. This often means making bold claims about particular positive aspects whilst ignoring other less palatable ones. Where the negative aspects manifestly outweigh the positive ones, you have classic misdirection.

Good examples of misdirection are those of making relative comparisons that are true in and of themselves, but don’t really mean much out of context. Another flavour is featuring positive aspects and ignoring significant negative ones.

Example 1 – you could claim that your latest SUV is 26% more efficient than another SUV. But this could still mean that it does 24 miles per gallon and the other one does just 19.

It’s a shame – neither is remotely efficient when compared to most other vehicles.

Example 2 – your bottled water is sustainable because the PET plastic bottle is made of less plastic than your competitors and includes 20% recycled plastic too.

It’s a shame – that the (heavy) filled bottles are transported thousands of miles using fossil fuels. Much more than the real, but small, saving in fossil resources.

Example 3 – organic olive oil soap (pun intended…). Your packet looks homely and rustic (it’s also green) and highlights the local provenance olive oil in the product.

It’s a shame – that there’s only a few percent olive oil in the recipe, the majority of which is palm-oil derived (with no provenance) or other petrochemicals. There’s also more water than olive oil and more Hexyl Cinnamal – which is toxic to aquatic life.

Example 4 – Bamboo socks. These are sustainable because bamboo is fast growing and doesn’t require pesticides or irrigation to grow.

It’s a shame – that the bamboo’s grown in China and has a large carbon transport footprint. Oh – and don’t forget the Carbon disulphide used to process the bamboo. It’s very toxic to workers and the environment (see Paul D Blanc’s Uncommon threads: fashion’s deadly fabric).

3. Meaninglessness

This type of greenwash refers to claims and statements that have no inherent meaning.

Environmentally Friendly

These might be ‘environmentally friendly’ – nothing that isn’t actively contributing to the health and diversity of the environment is friendly, some things might be less bad – but none of them are friendly.

It’s a bit like saying that low tar cigarettes are more ‘lung friendly’ than high tar ones; marginally less damaging perhaps, but not friendly.

All natural

‘All natural’, or ‘chemical free’ are similarly meaningless. Natural things aren’t necessarily safe (many poisons are natural) and everything in the world is made of chemicals.

Biodegradable

‘Biodegradable’ is an often-abused term. It can be a good thing (and does in fact have definitions to support it). But its impact depends on whether the substance in question properly degrades in real-world environments – and crucially what it degrades to. Some compounds biodegrade to other toxic substances.

Is greenwashing really damaging?

Greenwashing is damaging at several levels. Firstly, it’s inherently untruthful and undermines trust and reputation. If you’ve bought a product or service believing it to represent a low impact or ethical choice, and it turns out to be the opposite – you have the right to feel let down, betrayed, even.

But the impact of this bad behaviour goes wider. Because the most egregious false claims are often discovered and called out, there is a wider environment of distrust leading to widespread underreporting or ‘green modesty’ or ‘greenhushing’ (where companies keep quiet about meaningful sustainability achievements).

Avoiding greenwash

So, if there are a multitude of ways to get it wrong, how can you make valid claims?

Some of the simplest and most practical guidance for producing responsible messaging was produced by the UK Government’s guidance for environmental claims, which notes that legitimate claims are:

- Clear

- Accurate

- Substantiated

But when it comes to assessing messages, whether they are ones you see on products or are thinking of putting on your own we have the following suggestions:

- Be sceptical – put yourself in the shoes of a critic: would you be able to defend the assertions and claims you have made?

- Be self-critical – put yourself in the shoes of a competitor, an NGO, or a scandal-seeking journalist reading your messages: are you still happy with them?

- Err on the side of caution – it is better to say less and be able to defend it, than to say more and have difficulty supporting if challenged.

Sustainability-related performance and choices are often complex, nuanced and/or require inherent trade-offs between relatively less bad options. These are difficult to communicate in simple and positive messages that fit people’s valuable and limited attention spans.

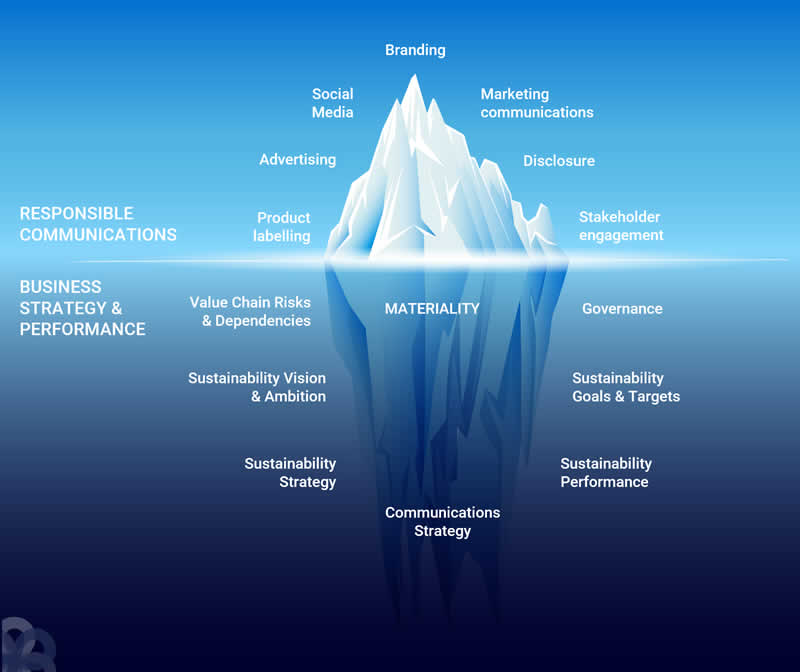

Greenwashing is effectively the antithesis of following a materiality-based approach (focusing on all the important issues in your value chain). But if you follow these principles with care, you’ll be on the right side of the great greenwashing watershed.

To-date, claiming environmental credentials has been somewhat of a niche activity. But now that consumers, governments and even a few companies are waking up to the power of blah blah blah – greenwashing really has gone mainstream.

There’s so much activity it can be difficult to keep up and not be overwhelmed with who’s claiming what and on what basis – or perhaps more importantly – what lack of basis.

So why does this matter?

You might consider yourself an old hand at greenwashing. Perhaps you’ve made some truly outrageous claims with virtually no basis in fact. You think you’re top at the top of your game. But you have a little voice in your ear: ‘what if someone else is making claims even more mendacious than ours?’

It’s time to get professional. So, we’re pleased to announce the new Real Greenwash KitemarkTM.

‘The thing of which I have most fear is fear.’

Michel de Montaigne

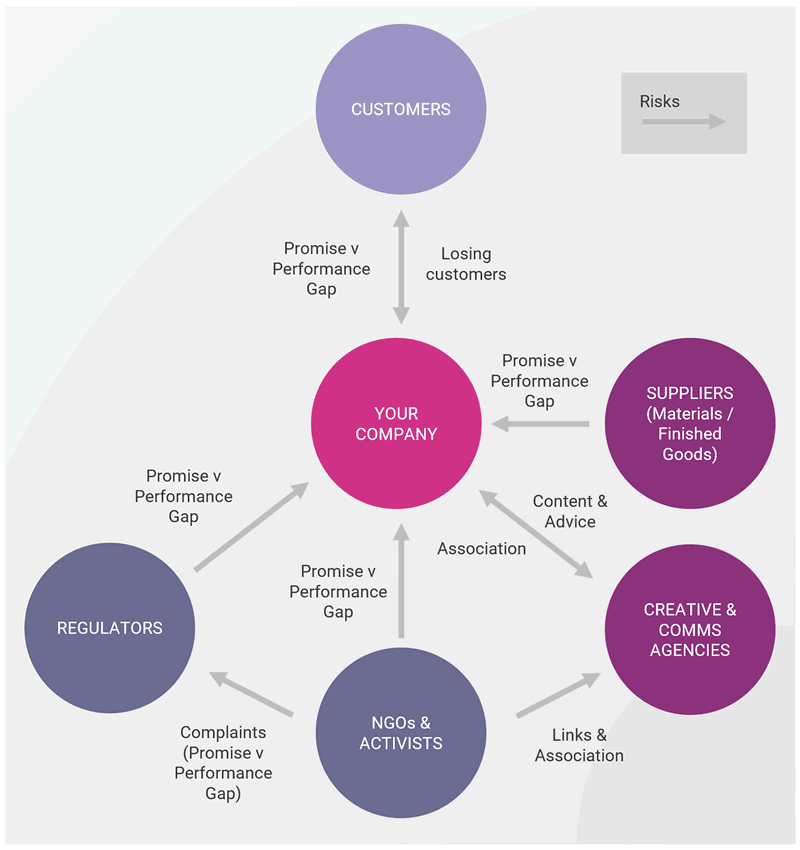

Greenwashing can create various dimensions of risk, but these are often overlooked, and their implications are insufficiently examined.

Greenwashing may appear as simply irritating, but it actually causes a range of harm and presents multiple business risks, to the company which communicates it, but also to companies involved in creating it and those associated with it.

Greenwashing has traditionally been associated primarily with marketing and sales-related messages, but it is also being increasingly seen as something which can arise from strategic corporate communications and formal sustainability reporting and disclosure.

The nature of focus on what constitutes greenwash is also changing, moving from an assessment of whether specific claims or statements are clear, accurate and substantiated towards a wider assessment of claims, ambitions or implications for corporate performance within the context of the company as a whole.

What are the risks of greenwashing?

The most significant risks related to greenwashing can be placed into two distinct (but overlapping) areas.

Regulatory risk

Marketing and sales communications that break regulatory codes can result in adverts being banned and/or fines and the CMA (Competition and Markets Authority), the UK’s competition watchdog, has extensive and growing powers to censure companies for other types of misleading communications.

This is a prominent, but shorter-term risk – several of our customers have asked us to help them reduce risks specifically related to sustainability communications.

Reputation and brand risk

This is perhaps a much larger risk, as more is potentially at stake, and it can have longer-lived (albeit related) impacts than a regulatory breach.

Reputaton is an important asset and driver for many businesses and for the communications and creative agencies who support them with their messaging. However, the level of awareness about the risks appears to be low.

Reputation and brand often provide the greatest areas of opportunity and value in sustainability for companies. Reputation is a largely intangible attribute – but also potentially hugely valuable. It is often closely linked to sustainability performance. Greenwashing, or the perception of greenwashing, places this at risk.

Who are the important stakeholders for greenwashing risks?

The landscape is relatively complex as greenwashing risks can arise across different activities and areas in the value chain. They are summarised below.

Table 1. Greenwashing risk routes and relationships

| STAKEHOLDER | PRINCIPAL RELATIONSHIPS & INTERESTS |

| Regulators; CMA (UK), ASA (UK) EC (EU), FCC (US) | Protecting the interests of consumers and businesses, market integrity, focus on communications and behaviour of the ‘the company’. |

| Consumers / Customers (B2B) | Environmental and social performance of the company and the relative perceived merits of its products or services. |

| NGOs / activists | Pursuing their agendas, calling out examples of bad practice/perceived malfeasance in companies –their partners or suppliers. |

| Investors | ESG performance and risk to investment judgements for ‘the company’ which may already be held or is an investment prospect. |

| Company suppliers | Providing materials/labour/finished goods – a source of potential risk to their customers via their activities and material sourcing. |

| Creative/professional services suppliers to companies | Providing services (marketing, communications, advertising, sustainability). Source of potential risk to ‘the company’ in greenwashing through advice/content development. |

| The ‘company’ | Interested in protecting its reputation, avoiding regulatory action. Source of potential risk by association to creative/professional agencies, services companies and investors. |

Challenges for companies

Drawing out the implications for companies, managing potential greenwashing-related risks requires a focus on the company’s sustainability performance (across the value chain), which in turn is closely integrated with all communications related to sustainability and environmental issues. This extends to screening the performance of suppliers – including creative agencies which provide support and input to external communications.

Calculating the level of risk – as always with risk management, is complex. You can be hit with a fine or other regulatory action and that will highlight a bad news story that can affect your brand and reputation. The severity of this impact will depend upon a number of factors including:

- The perceived magnitude of the problem.

- How many people are affected.

- Duration of the problem (in turn related to…)

- The ability to take mitigating action – and demonstrably taking that action.

- Cumulative effects (has something similar happened before?).

These criteria imply the risk can be managed. However, any single issue, if perceived to be high impact by stakeholders, can be sufficient to cause a great deal of harm, and it’s these ‘long-tail’ risks, of low likelihood but high impact, that can be particularly damaging.

Challenges for the creative industries

Over the spring and summer, we’ve been talking to creative agencies, and many are aware of some of the reputational risks related to greenwashing. Like some of the other risk exposure routes outlined above, these involve both risk to the creative company and risk from the creative company.

These can include being involved in creating copy, content, and campaigns that breach rules, but also working for a company whose wider behaviours and performance may represent a risk to them by association.

A good example is provided by Clean Creatives, their:

‘pledge commits agencies, creatives, and strategists to refuse any future contracts with fossil fuel companies, trade associations, or front groups.’

Recently this has led to direct action protests against PR/creative giant Edelman’s ties to ExxonMobil (an Edelman customer).

So here we can see parts of the creative industry calling out perceived greenwashing and collaboration in greenwashing by their own.

Risk perception gaps

A risk perception gap is the distance between an informed and measured assessment of risk and the level of risk perceived/understood by the relevant parties/actors.

Through recent work and related discussions, we have seen at least three significant risk perception gaps.

1. Awareness and understanding

In general, the phenomenon of greenwashing is widely recognised and at one level understood to relate to the fundamental sustainability performance of a company (but see 2 below) – that companies without good sustainability performance are at risk when they seek to overclaim or make partial claims.

Less well recognised is that greenwashing can also be a risk for companies that are in principle ‘better performers’. A company can have good sustainability credentials but still produce communications which are not compliant with regulations related to greenwashing.

2. Focus

Many companies are aware of the risks related to greenwashing. However, anecdotally, we have found this is often at a generic level and frequently seen only through the lens of corporate and marketing communications – as opposed to the inherent sustainability management performance (and disclosure) of the organisation.

3. Responsibility

From our conversations with marketing, PR, and creative agencies, we have found that all are aware, at least in theory, of greenwashing and most are very keen to avoid it. However, a small number feel the risk lies with their client – that if the client signs off on copy/content which is not compliant then they have nothing to worry about. This I find a startling, short-sighted and short-term approach.

4. Materiality

Materiality (focusing on the issues that are important) is a core concept in sustainability (and greenwashing), but one that is often, if not poorly understood, certainly lacking in its observance and practice. To manage risk adequately, all important sustainability-related issues must be included in any assessment. If a company is making a claim regarding sustainability issues or performance, it is critical that all material issues are also carefully considered and assessed. In many cases these are not – see below.

The Clean Creatives example highlights a focus on carbon/climate-related issues. In the month that has seen the warmest global temperatures ever recorded, and severe heat in Europe, the US and beyond, it’s of course vital.

But if your assessment of association risk focuses only on carbon (and many we’ve seen only do this) then you are missing other material (priority) issues which also present possible risks.

To put it simply, if you screen a possible client based only on climate-based risks then how will you spot child labour, human rights, modern slavery, toxics, biodiversity, habitat loss, resource exploitation or other risks?

It’s somewhat unclear why the approach is so partial, it might be related to the maturity of understanding of sustainability issues, or the symptom of a lack of attention and resources available for this activity.

5. Reliance on standards

One of the ways to ensure communications on sustainability are responsible, and avoid greenwashing, is to use standards and certifications. The best ones provide robust third-party accreditation of performance.

But what happens if they are weak – or perceived as weak?

Following the public release (following a FOI request) of a 2020 Environment Agency report on agricultural pollution, the NGO River Action has claimed that the majority of the polluting farms in the study had Red Tractor certifications, and therefore that Red Tractor membership was not a good indicator of environmental performance. Red Tractor claims the report does not show this and contests the negative claims.

This sort of claim and counterclaim is not unusual. However, the twist in this case is that River Action has filed three complaints to the ASA (Advertising Standards Authority) claiming: “a strong body of evidence suggests that Red Tractor’s advertising, website and YouTube content is misleading consumers about the environmental standards with which its assurance scheme purports to guarantee compliance.“

The implications of this can be interpreted in several ways:

Firstly, that campaign groups will use any tools available – and anti-greenwashing powers are now sufficiently strong that they can be actively used to root out poor practices.

Secondly, a much wider implication relates to a reliance on standards. Advertisers are required to hold up-to-date and relevant evidence to support claims made. If a label such as Red Tractor fails to provide this function in the supply chain the value of the label moves from one of substantiation to one of greenwashing. So, if the ASA upholds the River Action complaint there will be consequences across the supply chain.

Managing greenwashing risks

No risk can ever be removed completely, but awareness coupled with action can be applied to manage and mitigate risks.

However, if we revisit our table exploring the routes to risk, we can look at the management responses available to companies and their suppliers.

Table 2. Possible greenwashing risk management responses

| RISK FROM | RISK TO | ROUTE / RISK | MITIGATION |

| Regulators | Company | Direct / Fines/regulatory action Indirect / Damage to brand reputation. | Improve material performance. Ensure claims match performance and meet codes. |

| Regulators | Creative/professional agencies/services | Direct / Fines/regulatory action (for own communications) Indirect / Damage to brand reputation (for work supplied). | Direct / Most risk to the company through divestment or access to/cost of capital. |

| Consumers | Company | Indirect / Risk through complaints to regulators Direct / customer boycotts Indirect / Damage to brand reputation. | Improve material performance. Ensure claims match performance and meet codes. |

| NGOs / activists | Company | Direct / Most risk to brand reputation via adverse media. | Improve material performance, genuinely manage issues. |

| NGOs / activists | Creative/professional agencies/services | Direct / Most risk to the company through divestment or access to/cost of capital. | Screen customers. |

| Investors | Company | Direct / Most risk to the company through divestment or access to/cost of capital. | Improve material performance. Accurate, transparent and material disclosure. |

| Company suppliers | Company | Direct potential risk from activities, finished goods and materials supplied. | Improve supply chain performance . Screen suppliers and performance manage. |

| Creative/professional services suppliers to companies | Company | Direct potential risk from creating greenwash advice or content. | Screen suppliers and performance manage. |

| Company | Creative/professional agencies/services | Indirect Risk from association. | Screen customers. Engage with and support customers. |

As can be seen, this simple analysis suggests two main areas of activity for risk management and mitigation, performance improvement (including compliant communications) and company screening.

Performance improvement

We’ve written at length about and sustainability issues and performance improvement (e.g. 2023 sustainable business trends and challenges – what to watch out for, and embedding sustainability in your business) as it’s the main purpose of the support we provide.

However, the list below provides a checklist of the key aspects that are required:

- Understand the strategic context – what are the actual risks and impacts of your business?

- Assess materiality.

- Develop a focus on the (material) issues that matter for your company and stakeholders.

- Develop long-term goals and targets for material issues/areas.

- Disclose progress and performance.

- Communicate and engage with stakeholders on what’s important and your progress – with credibility and transparency.

- Review – review and adjust your issues/focus and responses/performance.

Compliant communications

The key elements of responsible communications are to ensure that any copy or claims:

- Use precise language – avoid unjustified general claims, and be specific

- Apply sound logic – the claim must be entirely correct and tell the whole story of a product/service. If it only relates to a part of the product/service, it must not mislead about the overall environmental impact

- Supply good evidence – all of the claim (whether absolute or relative) must be backed with timely and relevant underlying evidence

Conclusions – managing greenwashing risks

Fundamental performance management provides the foundations for managing greenwashing risks and producing responsible communications. However, it’s often not visible and greenwashing is frequently only addressed at the ‘surface level’ of external communications.

The Responsible Communications Iceberg illustrates how responsible communications rely upon underlying business approaches and performance. Building trust, credibility and authenticity requires these underlying structures and delivery.

Avoiding greenwash is both a strategic and tactical endeavour.

At the strategic level, without meaningful overall strategy and verifiable performance then companies have a very shaky foundation to be making any sustainability claims in the first place.

Tactically – as noted above, even companies that might in principle have good underlying strategies and performance can still fall foul of greenwashing regulators if they do not comply with relevant regulations and codes.

The two levels cannot be separated or ignored.

While all communication has inherent risk, the companies with the best awareness of what risks exist, where they might occur and takes a careful, compliant, and strategic approach to their identification and management is most likely to avoid being accused of greenwashing.

Worldwide regulators are tightening up on strategic greenwashing to protect consumers, business and market integrity. As further examples arise there is more, we can learn about what regulators will tolerate and what they require of companies.

Put simply, any leeway for general feel-good statements, vague aspirations and unsubstantiated claims has vanished as the focus shifts from products and services to more fundamental strategy.

In this article, we review the major stakeholders with a stake in clamping down on greenwashing, take a look at three recent high-profile cases where adverts have been banned and examine the far-reaching implications of regulatory requirements for companies.

Who are the major players? (Stakeholders)

In the UK

The CMA

The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) is responsible for promoting healthy market competition and preventing anti-competitive activities in the UK. The CMA is tasked with investigating mergers, conducting market studies and investigations, enforcing consumer protection legislation, and overseeing the UK internal market.

At the end of 2021, the CMA’s Green Claims Code set out a clear, comprehensive framework for organisations looking to make environmental or sustainability claims in their communications. The CMA also conducts active investigations based on complaints received and initiates wider industry investigations into specific sectors where it suspects there are risks of structural or systemic challenges. To date, it has launched investigations into the fashion and FMCG sectors to assess the accuracy of environmental claims.

The ASA

“The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) is the UK’s independent advertising regulator. The ASA makes sure ads across UK media stick to the advertising rules (the Advertising Codes).”

The ASA administers two different codes on advertising differentiating between Broadcast Advertising (BCAP Code) and Non-broadcast Advertising which also includes Direct and Promotional Marketing (CAP Code). Both codes include rules on accuracy and truthfulness and include specific clauses relating to environmental claims and messages that ‘could be considered harmful or socially irresponsible’.

The Codes are consistent with the CMA’s guidance but have a more operational focus for advertisers. For example, ads with environmental claims must be clear and use terminology that the consumer is likely to understand. Research by the ASA suggests there is a widespread misunderstanding of terms in the general population. As a result, they place responsibility on the advertiser to ensure communications are clear.

Importantly, the Codes apply different standards to ‘absolute environmental claims’ and ‘comparative environmental claims’:

- Absolute environmental claims – includes claims such as green or environmentally friendly.

- Comparative environmental claims – include claims such as greener or friendlier.

The codes require a higher standard of evidence to back up absolute claims, the default being they are backed with robust evidence about the product’s entire life cycle.

If comparative claims are made, they should clearly state the basis of the comparison and make it clear which product or aspect of a product is being compared and what it is being compared against.

In Europe

In the EU, the European Commission takes the lead on regulation which is brought into law by member states. In 2022 the EU proposed amendments to Directive 2005/29 on Unfair Commercial Practices (UCP). This defines an environmental claim as:

“Any message or representation, which is not mandatory under Union law or national law, including text, pictorial, graphic or symbolic representation, in any form, including labels, brand names, company names or product names, in the context of a commercial communication, which states or implies that a product or trader has a positive or no impact on the environment or is less damaging to the environment than other products or traders, respectively, or has improved their impact over time”.

It extends the categories of product characteristics that are covered to: environmental or social impact, durability and reparability and specific practices are also considered misleading including: “an environmental claim related to future environmental performance without clear, objective and verifiable commitments and targets and an independent monitoring system”.

The EU Taxonomy Regulation (2020) – is designed to reduce fragmentation in sustainable financing practices across the EU, to prevent greenwashing in financial products and provide a common classification system (of language and definitions) on what can be considered ‘environmentally sustainable’. Together with the Green Deal it describes the direction and intent for Europe.

In March 2023 the European Commission proposed a new Green Claims Directive to address greenwashing. The Commission wants to enhance consumer awareness regarding the sustainability attributes of products or services. The objective is to provide consumers with greater assurance that products marketed on sustainability criteria fulfil these. This will also aid consumers in making informed choices on products and services by providing better quality information.

The proposals are to establish the EU’s first detailed rules and regulations for the validation of voluntary green claims and marketing communications, they include:

- criteria on how to prove environmental claims and labels

- requirements for claims and labels to be confirmed by independent and accredited verifiers

- new governance rules on labelling schemes to confirm they are clear, transparent and dependable.

The directive would require companies to use widely recognised scientific evidence and accurate information when making environmental claims, consider all relevant environmental aspects and impacts, demonstrate the difference between their product and others in environmental performance using common practice standards, and have all environmental labels independently verified and certified before being presented to consumers. Companies found in violation of the directive could face fines of up to 4% of their profits and be barred from public procurement contracts.

Taken together these have added up to a much stricter environment for misleading or inadvertent communications.

In the US

In the US various laws and regulations govern environment/advertising, they include:

- Federal Trade Commission Act (1914) – underlying legislation

- State Laws – different states have specific laws – notably California’s 2008 Green Chemistry Initiative

- Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Green Guides (1992 & 2012) – guidelines for businesses on environmental claims

- National Advertising Division – covers advertising claims

- The Climate and ESG Task Force (2021) – a SEC Task Force

- Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) – a powerful federal agency responsible for protecting investors and maintaining the fair and orderly functioning of markets.

In May 2023 the FTC announced they were revising their Green Guides to provide the agency with a stronger basis for bringing cases and clarifying when misleading marketing on environmental or wider sustainability grounds contravenes federal law.

Consumers

hile most regulators mentioned above have a remit for consumer protection, consumers also have an active role to play. A significant proportion of consumers want information to inform their choices and behaviour, and some make buying decisions according to perceived performance on social and environmental criteria.

In many ways trying to sway consumer opinion is one of the major drivers of greenwash.

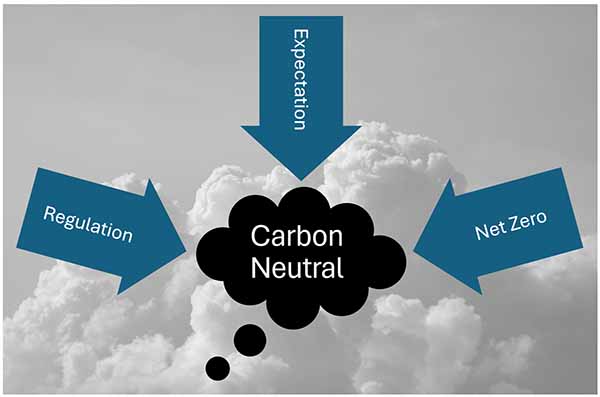

In the UK, the ASA commissioned research into consumer understanding of environment-based terminology used in advertising. We’ll be writing about this area in more detail, but it’s interesting to note some key findings. They found:

- Environmentally themed terms and claims often led to misunderstanding in general advertising contexts

- The terms Carbon Neutral and Net Zero were not well understood and were often seen as synonymous, but Neutral and Net were often both perceived as direct reductions in carbon

- The perceived prevalence of ‘greenwashing’ diminished trust and credibility

- Claims had little direct impact on purchases, however, they could have favourable impacts on brand reputation

NGOs

NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) have played a role in raising consciousness about environmental and social issues and holding organisations to account when their performance does not appear to match claims or stated intentions.

But sometimes they also take more active roles, for example, NGO Client Earth has participated in direct legal action in several cases including against KLM and Total and made a complaint about BP to the OECD.

Investors

Increasingly investors have been adopting ESG and sustainability criteria, for three main reasons. Firstly, because this area is receiving much attention and they need to respond to changing market requirements, regulations and scrutiny. Secondly, because they can make money, and thirdly because it makes good long-term risk management – or it can do if done well. Investors require good quality data and assessment of plans and the company’s ability to execute. Greenwashing muddies the waters and undermines confidence in these investment areas.

What’s the focus of regulators?

There’s a surprising level of consistency across different regulators internationally. While there are differences in the style of regulation, they have common approaches to what’s considered misleading. In response to the increasing prevalence of greenwashing, they are also taking increasingly tougher stances on infringements.

Here we examine three recent examples of adverts banned in the UK to see how the regulations and guidance are being applied in practice – and what we can learn from this.

HSBC, posters in bus shelters – October 2021

The UK Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) banned a series of HSBC’s sustainability-focused adverts, stating that they were misleading consumers. The first ad stated:

“Climate change doesn’t do borders. Neither do rising sea levels. That’s why HSBC is aiming to provide up to $1 trillion in financing and investment globally to help our clients transition to net zero”.

The second advert stated:

“Climate changes doesn’t do borders. So in the UK, we’re helping to plant 2 million trees which will lock in 1.25 million tonnes of carbon over their lifetime”.

The ASA received 45 complaints claiming the posters were misleading because they excluded significant information about HSBC’s contribution to greenhouse gas emissions.

The ASA stated: “The CAP Code required that the basis of environmental claims must be clear and that unqualified claims could mislead if they omit significant information.”

But their ruling went much further than that, stating that they thought consumers would understand the key claims as HSBC making:

“…a positive overall environmental contribution as a company. As part of that contribution, we considered consumers would understand that HSBC was committed to ensuring its business and lending model would help support businesses transition to models that supported net zero targets.”

The ruling showed that the ASA looked to HSBC’s Group Annual Report and Accounts that indicated that emissions related to the customers it financed totalled at least 65.3 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent per year for oil and gas activities alone and would be much higher when other investments were included – including HSBC’s funding of thermal coal.

The ASA concluded that the adverts omitted material information and were therefore misleading. The ruling demanded that HSBC ensures all “future marketing communications featuring environmental claims were adequately qualified and did not omit material information about its contribution to carbon dioxide and greenhouse gas emissions”.

Lufthansa, poster – June 2022

The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) banned an advertisement by Lufthansa featuring the tagline “Lufthansa Group Connecting the World. Protecting Its Future.” for representing a misleading impression of environmental impact.

The ASA argued that “The CAP Code required that absolute environmental claims must be supported by a high level of substantiation.”

They rejected Lufthansa’s claims that the campaign was referring to specific steps to reduce environmental impacts – referring to the ‘protecting its future’ claim saying this was not supported by the actions described.

The ruling highlighted aviation’s ‘substantial contribution to climate change’ and also acknowledged the impact-reduction steps being made by Lufthansa to pursue their stated goals of becoming carbon neutral by 2050, and reducing carbon emissions in half by 2030. However, they then stated:

“Many of these initiatives were targeted to deliver results only years or decades into the future. We also understood that there were currently no environmental initiatives or commercially viable technologies in the aviation industry which would substantiate the absolute green claim “PROTECTING ITS FUTURE”, as we considered consumers would interpret it.”

Etihad Airways, Facebook ads – October 2022

The two adverts included video and text and the claim: “… we’re taking a louder, bolder approach to sustainable aviation”. One ad mentioned earning Etihad Guest Miles “every time you make a conscious choice for the planet”.

And the second: “We’re taking a louder, bolder approach to sustainable aviation” in the body of the text and “… we’re cutting back on single-use plastics and are flying the most efficient planes” in the accompanying video.

Both included the statement: “Environmental airline of the year”.

As with the Lufthansa case, the ASA highlighted that:

“The CAP Code required that absolute environmental claims must be supported by a high level of substantiation.” And that: “consumers would understand the “sustainable aviation” claim to be about Etihad’s whole business.”

Again, their ruling made an acknowledgement of steps towards impact reduction but pointed to the high impact of the aviation sector on climate change and that the remedial steps might only deliver results years or decades in the future, adding:

“Initiatives such as reducing single use plastics and using more efficient aircraft were not adequate substantiation to evidence a ‘sustainable aviation’ claim.”

Once more, they highlighted that there: “were currently no initiatives or commercially viable technologies in operation within the aviation industry which would adequately substantiate an absolute green claim such as ‘sustainable aviation’”.

They concluded that the claim exaggerated the (reduced) impact that flying with Etihad would have on the environment and that the ads breached the Code.

Air France, Google ad – July 2023

Air France’s Google ad was seen in July 2023 and stated “Air France is committed to protecting the environment: travel better and sustainably”.

The ASA challenged “whether the ad gave a misleading impression of the advertiser’s environmental impact”.

In the ruling, the ASA stated that Air France-KLM did not provide a substantive response to their enquiries.

The CAP code considers that this was an ‘absolute’ claim – and therefore:

“expected to see a high level of evidence which demonstrated how Air France were protecting the environment and making aviation sustainable.”

The issue here – as with previous rulings for other airlines is that the regulator’s assessment is that the aviation industry produces high levels of CO2 and associated climate damage and also that there are no currently available/commercially viable technologies in the aviation industry that can back up an absolute claim.

Or put another way, you can’t make an absolute claim for an unsustainable industry.

What does this mean for company communications?

Many specific examples of greenwashing are found lacking or misleading because they provide insufficient detail and/or evidence to back up the specific claim, but in general, the claims are assessed at the level of product or service performance.

While this remains the focus of much current activity, the recent rulings highlighted above also suggest more fundamental implications.

In each of the three cases above the ASA referred to the wider strategic context that the businesses operate in or put another way ‘strategic greenwashing’.

In each of the cases above the communications fell short because they had not proven the net environmental impact of the businesses as a whole were not harmful.

Therefore, the implications of the rulings – and their underlying assessments – is that the company’s sustainability strategies are fundamentally implausible.

In the case of HSBC, the ruling focuses on the mismatch in scale between specific interventions and wider mainstream business activity and investments.

This is known as the greenwashing sin of misdirection, which could be addressed by a more integrated and strategic approach to business strategy and implementation. In the absence of this HSBC or others in a similar position would need to roll back the scale of their claims.

For the airlines, the ASA was clear that at a sector level, there is no way of substantiating an absolute claim such as ‘sustainable aviation’.

In terms of greenwashing regulation, the focus is becoming more strategic, representing an apparent move from tests upon factual content to a wider test of plausibility. Plausibility is related to wider strategic context, company strategy and its ability to execute.

This can also be seen as more consistent regulation. A wider interpretation of greenwashing – assessing specific environmental claims against overall company performance (and long-term ability to deliver) aligns more broadly with public understanding of what greenwashing means.

Avoiding strategic greenwashing – how should companies respond?

Good sustainability communications require a coherent narrative, focusing on the material impacts and activities of the business and delivering tangible improvements in performance. These two elements are intimately related but can arise in different ways.

Sometimes the narrative builds from the ground up, i.e.:

We have developed our strategy and are executing our associated plans, as a result we can demonstrate changes in sustainability performance – so what should we disclose/communicate about this?

In other situations, the communication requirement originates at the marketing or brand level, where the question asked is:

What position can we take / claims can we make about our product or service in sustainability terms?

If the answer is not very much without changing performance, then attention shifts upstream to examine what might be changed.

While these two different examples come from different origins within a company they converge in the same place – namely strategy.

The fundamental solution to the symptoms highlighted in the case studies boils down to two main courses of action:

- Tailor your environmental/sustainability claims to fit your actual performance. Performance must apply to the entire business and value chain and not be overstated.

- Improve your overall performance – that will provide the platform to make more powerful, valuable, and accurate claims.

Both require strategies that are fit for purpose and able to deliver on your long-term objectives.

Communicating well on sustainability while avoiding greenwashing can be confusing. Badges and accreditation schemes can provide a useful way to demonstrate third-party accreditation of performance.

But what if the badge fails to deliver expectations or standards?

Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) and Red Tractor have received criticism in recent years and now B Corp is in the spotlight again after high-profile member Dr Bronner’s very publicly quit the scheme.

Third-party sustainability schemes and certifications aim to offer transparency and promote environmental and social responsibility. This is a hugely difficult task at the best of times. Even the efforts of sophisticated ESG rating agencies produce ratings and scores of uncertain value.

The schemes are fraught with tensions between trying to promote and enforce standards, maintaining integrity and balancing complexity with relative ease of access.

At the same time, they are trying to build scale. If they are to have a significant impact, then they need to grow beyond small-scale, niche and purpose-led businesses to large multinationals. This is where many of the tensions arise. Dr Bronner’s, among others, have objected to Nestle’s membership of B Corp through their Nespresso brand. In 2020 Nespresso was accused of having coffee suppliers using child labour, and the packaging-intensive capsules have long been controversial in environmental terms. More recently, B Corp has launched new standards.

Criticisms of schemes include:

- Possible potential conflicts of interest – when schemes rely upon membership and certification fees

- Limited accountability – often weak or limited enforcement of standards once companies are admitted

- Standardisation – criticism of weak standards (as above) or dilution to accommodate more businesses

- Consumer misunderstanding and complacency – consumers don’t always understand all the issues and place trust in ‘badges’ this can allow companies to avoid further scrutiny

- Cultural bias – imposing Western-centric standards that may not fully account for local contexts, traditions, or needs

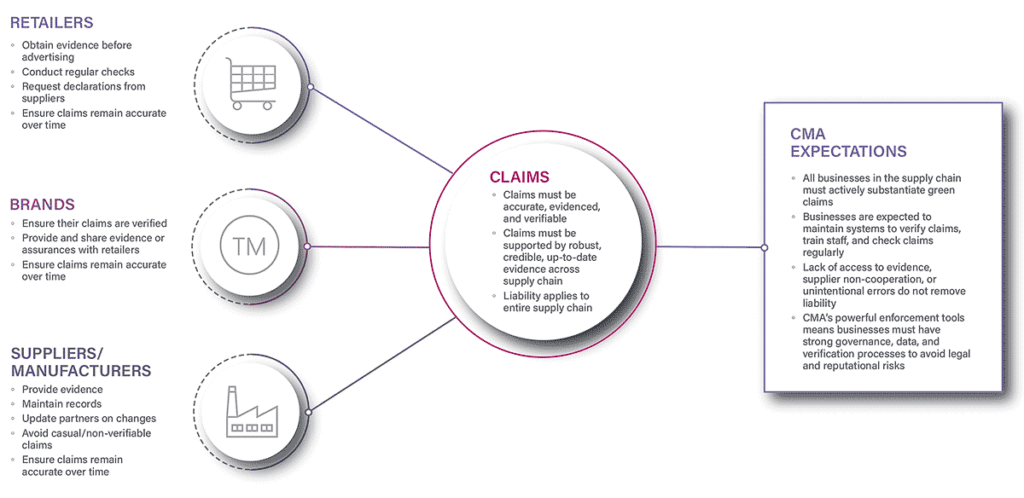

Why Green Claims Need a Value Chain Approach

We (not uniquely) have long emphasised the importance of taking a strategic and value chain approach to making green claims, and in January 2026 this point was powerfully (re)stated by the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) in new guidance on making green claims and the supply chain.

A quote from the CMA captures the main message well:

“If you are unable to obtain the information needed to satisfy yourself of the accuracy of a claim, you should consider whether you should make the claim differently, in a way you can verify.”

I’ve highlighted some of the key aspects and considerations emphasised by the CMA and the illustration below captures some of the most important points.

The core principle is:

1. Claims must be accurate, evidenced, and verifiable.

While this has always been a central principle of the Green Claims Code, the CMA’s most recent guidance underlines that, secondly:

2. Liability applies across the entire supply chain.

This has also always been the case, but the CMA sees the need to re-state and emphasise that this wide scope applies to claim substantiation:

3. Claims must be supported by robust, credible, up‑to‑date evidence across the supply chain.

The other key aspect the regulator highlights is with regard to the intention behind the claim.

When speaking or taking part on panels I’ve regularly been asked questions like “what if our intentions were good” or “does it matter if we’ve done some due diligence?”.

Here, again, the CMA is clear, the law does not require intent (meaning it doesn’t care about intent) and unwitting or innocent breaches are still breaches. It also states that “due diligence” is not a defence in civil cases.*

The CMA also provided some rare insight into its action. It reiterates that businesses should already understand the rules, especially where guidance already exists and that it’s more likely to take action (*) where:

- businesses lack proper internal processes for verifying claims

- businesses fail to correct issues proactively or do not provide consumer redress.

It could be argued that none of this is especially new, or surprising. However, the regulator publishing guidance provides some insights into what it sees as important, where it is perhaps getting frustrated/might take action and some of its current concerns.

The actions and performance of many of the key actors in the market are lagging behind regulatory requirements and expectations, therefore this is perhaps a salutatory warning to shape up or suffer the consequences.

* NOTE: We provide insight from a sustainability perspective, NOT legal advice or legal opinion of any sort. Refer to your legal team/advisors for legal advice.

UK Strengthens Enforcement Against Greenwashing: What Businesses Need to Know in 2025

Recent updates in UK consumer law have significantly strengthened action against greenwashing. The Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers Act (DMCC) 2024, effective from April 2025, gives the Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) new powers to directly penalise misleading environmental claims, with fines up to 10% of global turnover.

Greenwashing is now explicitly unlawful, and liability extends across supply chains. The Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) has also updated its codes to align with these changes. Together, these reforms create a tougher regulatory environment, making it easier for authorities to crack down on false or exaggerated green claims.

What does this mean for greenwashing?

It depends upon your outlook. In recent years the CMA has been clear about increasing its scrutiny on environmental/sustainability claims made by businesses. The DMCC provides the CMA with much greater enforcement powers and the guidance suggests that green claims will remain a priority. Under the Act, greenwashing is considered to be an ‘unfair commercial practice’ and is therefore deemed unlawful.

Continued focus on greenwashing

In March, the CMA outlined its enforcement priorities ahead of the new powers coming into force. The organisation suggested that early enforcement would focus on the more ‘egregious breaches’.

The example priorities in the first column below are quoted from the CMA’s blog (https://competitionandmarkets.blog.gov.uk/2025/03/10/our-new-consumer-enforcement-regime/), the second column provides our interpretation.

| CMA examples (direct quotation) | What might this mean for greenwashing? |

|---|---|

| aggressive sales practices that prey on vulnerability | The UCP (Unfair Commercial Practices provisions in the DMCC) describe consumers interested in reducing environmental impacts and suggests that they might be vulnerable (credulous) to inaccurate messaging on the environment |

| providing information to consumers that is objectively false | Misleading green claims often include false information. |

| contract terms that are very obviously imbalanced and unfair | N/A |

| behaviour where the CMA has already put down a clear marker through its previous enforcement work | The CMA has previously made green claims a focus. |

| where the law tells us that a practice is always unfair”. | Described by Schedule 20 of the DMCCA), does not appear to specifically relate to green claims. |

Changes in law

Two changes introduced by the DMCC Act relates to green claims / greenwashing. They stem from the revocation and restatement of the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 (CPRs) by the new Unfair Commercial Practices (UCP) provisions in the DMCC.

Extending consumer law

There is now a broader value chain concept applied to ‘commercial practices’ that includes claims and statements made about branded products supplied by third parties. Suppliers must be able to substantiate claims they make and all businesses in the supply chain are potentially liable for misleading claims.

Changing legal tests

The Act simplifies legal tests, making it easier for the CMA to take action. For example, if a business omits material information on a product, it is now automatically unlawful. The CMA no longer needs to prove that such omissions affect consumer decisions. This can include the omission of material information on a product’s environmental impact.

Tougher regime for enforcement

Direct enforcement is another major change under the new Act. The CMA can now determine breaches of consumer law and issue penalties with having to go through the counts.

It’s currently unclear how the new enforcement regime will play out. To date serial green washers have benefited from the fact that taking legal action is a lengthy and complex process. Now however, the new direct powers granted to the CMA may change that – although sanctions can be still be appealed through the courts.

What are the penalties?

The CMA has the power to issue fines. The level of fines will be determined by several criteria including the size (turnover) of the company, how serious the breach is, and other related factors including the level of harm and culpability (which can be exacerbated by, for example, having ads banned by the ASA). These are all descried in published guidance.

Maximum fines are up to £300,000 or 10% of global turnover – whichever is higher. There is a new settlement procedure that can allow for a reduction in fines if certain conditions are met – one of which is an admission of wrongdoing.

Advertising Code Changes

In early April 2025, the Advertising Standards Authority (ASA) updated the UK advertising codes (CAP and BCAP Codes) to align with the DMCC’s UCP provisions.

The ASA is in the process of updating its guidance and advisory resources to reflect these changes, in the meantime it refers advertisers to CMA’s guidance on the UCP provisions.

Most rules on misleading advertising remain substantively the same, but the advertising codes have been amended to closely reflect the updated legal framework in the DMCCA.

TAKEAWAYS

What can we learn from these developments?

- A higher overall risk environment for businesses (recognised by the CMA).

- Higher financial penalties for transgressions.

- Green consumers are considered as a potentially vulnerable group – because they are interested in environmental claims and could be taken in by them.

- There is coordination between regulators – when considering a case, the CMA would look for any previous action ASA rulings, and if present, this would be seen as an aggravating factor.

- Basic green claims guidance on what constitutes greenwashing remains the same.

- The new Act represents an increasing focus on greenwashing, and higher risks for those organisations found to be misleading consumers with environmental claims. The dangers of greenwashing, and the need to ensure that consumers receive clear, accurate and substantiated information mean that advertisers and marketers need to be ever more vigilant, careful and creative to ensure that they undertake responsible communications on environmental performance.

Responsible Communications Support

Coffee ads banned for misleading ‘compostable’ claims

Fashion Industry Greenwashing Review – CMA Secures Pledges | March 2024

The UK’s CMA (Competition and Markets Authority) has issued an update (27/03/2024) on their 20-month probe into ‘green’ claims in the fashion industry.

The investigation had previously named ASOS, Boohoo and George (Asda) and the update reveals that these companies have signed formal agreements to ‘use only accurate and clear green claims’.

The CMA indicates that these undertakings require commitments in several areas to change the way that they describe, display and promote green claims, including:

- Claims – all claims must be clear, accurate and not misleading

- ‘Green ranges’ – must be clearer. The criteria for inclusion must be clearly described and include descriptions of the minimum requirements. Products should only be included in environmental ranges when they meet all the relevant criteria.

- Imagery – the use of natural imagery must not be used to suggest better environmental performance than can be demonstrated.

- Fabrics and content – these must be clear and explicit, so should include ‘recycled’ or ‘organic’ rather than ‘eco’, ‘responsible’, or ‘sustainable’ and should clearly display the percentage of ‘recycled’ or ‘organic’ fibres.

- Use of filters – if a customer searches for specific criteria like ‘recycled’ then only products made from ‘predominantly recycled materials should be shown.’

- Environmental targets – these should provide details and ‘must be supported by a clear and verifiable strategy, and customers must be able to access more details about it’.

- Accreditation schemes – statements about accreditation schemes and standards must make it clear whether an accreditation applies to specific products or to the company’s wider performance.

TAKEAWAYS

What can we learn from these developments?

- Considering the implications of this, if it were a school report it would be firmly in the category of ‘Could do better’. The regulator has spelt out specific conditions and requirements that the companies must meet – and by implication, these are needed because they have not so far been meeting them.

- The 3 companies must provide the CMA with regular reports to demonstrate compliance with these commitments and how they are improving their internal processes.

- There is a wider warning – the CMA has issued an open letter to the industry, asking fashion retail businesses to review their claims and improve their practices.

Responsible Communications Support

Turning up the heat on the advertising industry | February 2024

Like other sectors, the advertising industry is facing increasing scrutiny over its environmental impact. But perhaps uniquely, the impacts are one step removed and are based upon involvement in and promotion of environmentally damaging sectors.

The increased attention has been substantially led by activists within the creative industries themselves, through initiatives like Clean Creatives, which has sought to raise awareness about advertising agency clients and their activities. It also encourages organisations and creatives working in the sector to refuse any future contracts with fossil fuel companies, trade associations, or front groups.

A recent report from Planet Tracker further turns up the heat on major advertisers by investigating their ownership and raising some key questions for investors about the companies they support.

The report, ‘From ADversity to ADvantage’, focuses the attention of investors and lenders in the financial sector towards the six global Holding Companies which own the bulk of major advertising agencies.

Planet Tracker notes that the top 10 investors own on average 43% of the five listed advertising holding companies and believes that these investors are complicit in allowing environmental damage if they do not press holding companies to refuse to work for clients with high environmental footprints.

In addition, the report finds that executive compensation in advertising holding companies is heavily tied to financial performance, with little or no link to client profiles or their impacts.

A common mantra of advertising agencies is that their relationships with high-impact firms can allow them to have a positive influencing role, working on the principle that it is better to be inside the tent….

But just how likely is it that advertisers, frequently engaged in specific areas of focus, are capable of influencing the strategic decisions and therefore ongoing environmental footprints of the companies they work for?

It seems unlikely that an international oil major would accept strategic advice on direction and business models from an advertising agency. Apart from anything else they don’t have the relevant expertise.

Planet Tracker’s report highlights several areas where it believes that the advertising industry’s continuing support for high-impact sectors presents not only association risk (see our overview of association risk) but also risks to revenue, staff retention, capital performance and intangible value – each of them relating to bottom line impacts that should be of fundamental concern to investors and lenders.

TAKEAWAYS

What can we learn from these developments?

From ADversity to ADvantage raises some important questions that agencies should consider:

- Do you need to have increased clarity, consistency and ready justifications for who you choose to work for?

- Will you be able to answer investor questions about your decisions and the performance of your high-impact clients?

- What share of the impacts of your clients should be assigned to you?

- Should advertising agencies be more able to demonstrate meaningful positive change through their engagements?

Responsible Communications Support

CMA Investigation – Unilver in the spotlight | December 2023

On the 12th December 2023, the UK’s CMA (Competition and Markets Authority) announced a formal investigation into Unilever. It will look at claims for cleaning products and toiletries after an initial investigation raised concerns.

This appears to be the first investigation stemming from a wider review launched in January 2023 when the CMA announced a greenwashing probe into the FMCG (Fast Moving Consumer Goods) sector. This was to consider if companies, large or small, were promoting products including food, drink, cleaning products and toiletries using environmental claims which were misleading consumers.

The CMA is concerned that “Unilever may be overstating how green certain products are through the use of vague and broad claims, unclear statements around recyclability, and ‘natural’ looking images and logos”.

The practice under investigation includes:

- Use of vague and broad statements that might mislead consumers about environmental impacts.

- Possible exaggerations of how ‘natural’ a product may be.

- Focus on single aspects of a product that might mislead about total environmental performance.

- Unclear claims on recyclability.

- Use of colours and imagery that may contribute to the impression that products are “more environmentally friendly than they actually are.”

CMA’s CEO Sarah Cardell said, “We’ll be drilling down into Unilever’s claims to see if they measure up”.

Reuters reported that shares in Unilever opened 0.7% down on the day of the announcement – although they rose again the next day.

The CMA is at an initial stage of its investigation and Unilever may not have broken any laws. The CMA will use its powers to gather more evidence and depending upon its findings may secure undertakings to change practices, take legal action or close the case with no further action.

TAKEAWAYS

What can we learn from these developments?

- 10 months after announcing a review, the CMA is now pursuing a formal investigation.

- The stated intent of regulators to clamp down on communications that mislead customers is being backed up by action.

- The potential non-compliances reflect common greenwashing issues.

Responsible Communications Support

Airlines – banned again | December 2023

On the 6th of December 2023 airlines hit the sustainability headlines again – and for the wrong reasons.

The UK’s ASA (Advertising Standards Agency) banned adverts from three leading airlines – what happened? – and what can we learn from these latest rulings?

Air France

Air France’s Google ad was seen in July 2023 and stated “Air France is committed to protecting the environment: travel better and sustainably”.

The ASA challenged “whether the ad gave a misleading impression of the advertiser’s environmental impact”.

In the ruling, the ASA stated that Air France-KLM did not provide a substantive response to their enquiries.

The CAP code considers that this was an ‘absolute’ claim – and therefore:

“expected to see a high level of evidence which demonstrated how Air France were protecting the environment and making aviation sustainable.”